Last Monday two major groups released a set of new guidelines designed to lower cholesterol. Now, it appears a major component of the guidelines — an online risk calculator — may be flawed, the New York Times reports.

Since the publication of the guidelines, two Harvard Medical School professors "evaluated the guidelines using three large studies that involved thousands of people and continued for at least a decade," the Times reported. They knew the patients' health status at the start and then they looked to see how many had had a heart attack or stroke in the next decade. How accurate was the new calculator in predicting risk? From the Times:

The answer was that the calculator overpredicted risk by 75 to 150 percent, depending on the population. A man whose risk was 4 percent, for example, might show up as having an 8 percent risk. With a 4 percent risk, he would not warrant treatment — the guidelines that say treatment is advised for those with at least a 7.5 percent risk and that treatment can be considered for those whose risk is 5 percent.

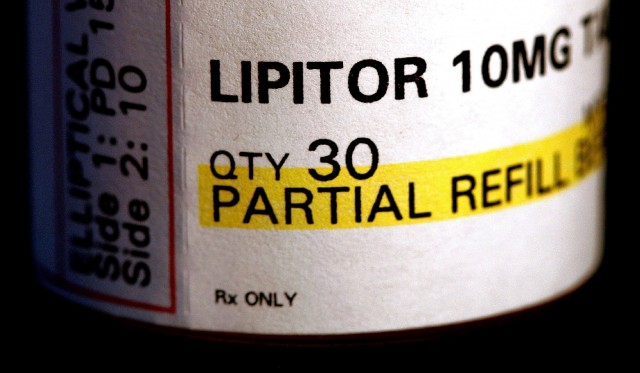

If this critique is accurate, it could mean that millions more people could be prescribed statins unnecessarily. That's a problem because "most of those people will see no benefits and have a lot of harm" from the statins, said Dr. Rita Redberg, a cardiologist at UC San Francisco. Redberg is also editor of JAMA Internal Medicine, where she has directed the Less is More campaign, designed to cut down on health tests or treatments where there are few (or no) benefits and lots of potential for harm.

In the case of statins, side effects include muscle problems, fatigue, memory loss and diabetes risk, Redberg says. And cumulatively, these side effects can happen to 20 percent of people taking the drug. Redberg is concerned that many people at low risk for heart disease will be prescribed a statin and be much more likely to experience harm than benefit from the drug.

"The chance of having a benefit from that medicine depends proportionately on how high your risk is of getting the disease in the first place," Redberg said. "If you're already at low risk to have a heart problem, it's very hard to make that even lower with medicines."