An estimated 6 million Californians will be eligible for insurance under Obamacare -- about 5 million through the Covered California marketplace and more than a million people via the Medi-Cal expansion.

Yet, just 16 of California's 58 counties have enough primary care doctors right now. To try to improve access, California legislators are moving bills to expand "scope of practice" for such midlevel health providers as pharmacists and nurse practitioners. In general, such bills would allow certain health providers to practice more independently. Right now, in many cases, they must be overseen by physicians. More autonomy could open access for underserved groups.

But some of those ideas are being hotly debated in Sacramento.

The toughest scope-of-practice sell right now seems to be nurse practitioners. Earlier this week, SB 491, which would expand nurse practitioner duties, failed to get out of committee. It will be up for a vote again next week. State Sen. Ed Hernandez (D-West Covina), an optometrist himself, joined KQED Forum Friday to discuss the bill. He said California needs to "utilize providers within their training" to help ease this "huge access problem in primary care."

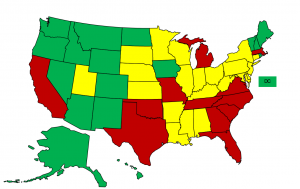

California, as it turns out, is among only a handful of states with the most restrictive policies (see map) around nurse practitioners and patient care. Paul Phinney, a pediatrician and president of the California Medical Association, said "allowing nurse practitioners to practice independently fragments care." He agreed there is tremendous primary care need, but said a better way to address the problem would be to "have physicians and nurse practitioners work collaboratively in teams."

Hernandez agreed a team approach is best, but pointed to many studies (he didn't say specifically, but this one from the Institute of Medicine is a good start) that have found nurse practitioners are "just as qualified" to provide safe primary care as physicians are. Right now, 17 states currently allow independent practice for nurse practitioners.