A study of rivers in the southeastern United States shows that as American cotton and tobacco farmers occupied once-forested lands, they wasted those fertile soils by causing them to wash away 100 times faster than the natural rate of erosion.

The paper, published online yesterday by the journal Geology, describes a new method that lets us learn the rate of soil erosion in “the forest primeval,” during the thousands of years before European farmers arrived. Having a single consistent laboratory test for this geological yardstick can help make agriculture sustainable.

If a region’s rate of natural erosion is known, farm agencies can teach farmers ways to tame erosion until it matches the primeval rate. That will almost automatically ensure that the area’s soil remains permanently fertile.

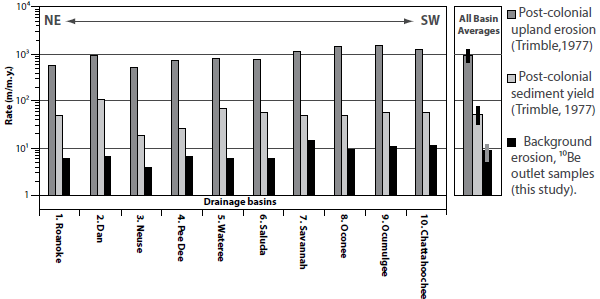

The study, by two geologists at the University of Vermont and a colleague at Lawrence Livermore Lab, looked at ten river watersheds in the Appalachian Mountains ranging from Virginia to Alabama. These went through a typical historical pattern—the forest was cleared by loggers beginning in the 1700s and then the land was farmed for cotton and tobacco. Traditional farming practices, which included tilling the fields each year with animal-drawn plows, led to rapid erosion and wore out the soil within a few generations.

This history is well known, but measuring that erosion isn’t easy. Regulators often use a formula based on the volume of sediment carried by a river. That method assumes the river system is in a steady state, with eroding dirt in the headwater area balancing the sediment passing out the river’s mouth.