Before social media and the ice bucket challenge, there were telethons. And of these televised pleas for money, perhaps the most famous is the one for muscular dystrophy, the one for “Jerry’s kids.” The MDA Show of Strength (as it is now called) has raised something like two billion dollars over the last 50 or 60 years and the money has been used to make great strides in helping people who suffer from this awful set of diseases.

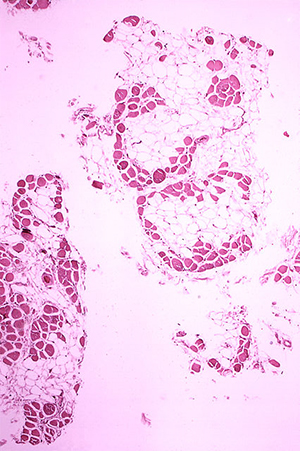

One of the most severe forms of this disease is Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy or DMD. Each year around one out of every 3500 boys (and a very few girls) is born worldwide with this devastating, muscle wasting disease. By the age of 10, many are already in wheelchairs as their leg muscles begin to give out and until recently, very few lived beyond their teens. Nowadays, with better treatments, they can live into their 30s, 40s and even 50s.

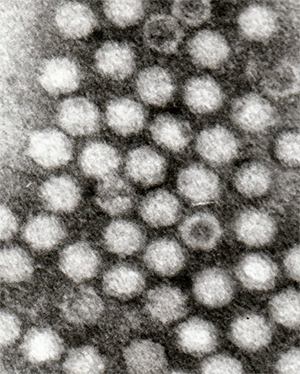

A new study reported in the journal Science gives hope that newer treatments may extend the lives of people with DMD even longer. In this study, Long and coworkers were able to repair the broken gene responsible for causing DMD in a fertilized mouse egg and so prevent the mouse from getting the disease in the first place.

Now DMD won’t be cured in humans in exactly this way any time soon. Because they treated the mouse embryo at the fertilized egg stage, the researchers knew very early on that the broken gene was there. If parents already knew at that stage, then there are better options already available.

For example, a parent who is a carrier could opt for in vitro fertilization, fertilizing the egg in a petri dish, and then using preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) to pick out only girl embryos who won’t develop the disease. Or if they want boys, they could select boy embryos that do not have the broken gene. While PGD is invasive, it is way less invasive than what was done in this study.