Civilization runs on refined energy and refined materials. While refined energy needs no introduction these days, most people need reminding that there is no economy without steady supplies of the most basic refined material of all: aggregate. A new map from the state government’s geologists is alerting us that California cities and regions must keep thinking locally to keep prospering.

The big three commodities that define aggregate are sand, gravel and crushed stone. They are essential for modern roads, whether white concrete or black asphalt, and for the deep roadbeds beneath them. They underlie foundations of all kinds: railroads, pipelines, skyscrapers and apartment blocks, gas station tanks, stadiums. Every pothole filled requires aggregate from somewhere, usually fresh from a quarry. Recycling is important, but limited.

You can’t use any old sand and gravel. Some deposits have chemically active minerals like pyrite; others are too weak or full of dust. Every construction project specifies a tightly controlled grade of material, and concrete, the mixture of aggregate and portland cement holding it together, is the most demanding. Concrete is 80 percent aggregate. The numbers that follow refer to concrete-grade aggregate.

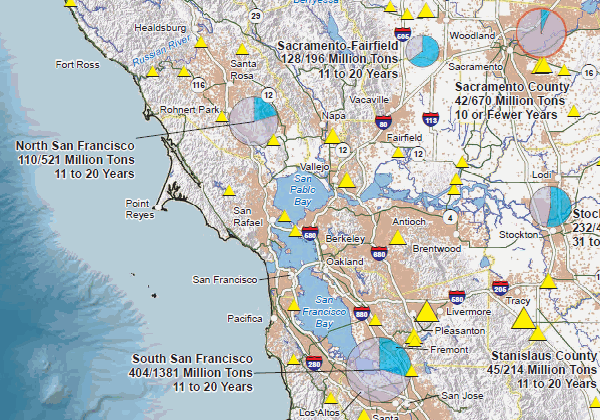

These days, the state goes through more than 200 million tons of high-grade aggregate every year, the equivalent of more than 7 million trips by large diesel trucks. Take a minute and consider the wear and tear those 7 million truckloads put on the roads; beyond that, trucking aggregate produces a huge amount of carbon emissions. And it adds 15 cents per mile to the cost of every ton delivered, or $7.50 per ton for the typical 50-mile haul on straight roads with little traffic. The material itself costs around $10 per ton for mining, crushing and other processing.

As California’s population rises, local regions must plan to reduce their waste output, decrease their water usage, and manage many other aspects of environmentally sustainable practices. Aggregate, too, needs to remain sustainable. The transportation costs of aggregate mean that it must always have a local source. Whether that source is artisanal aggregate from a boutique rock quarry or a big pit of good cheap river gravel—either is fine—is up to your local and regional jurisdictions. And quarries aren’t awful things; once played out they can be repurposed for all sorts of uses.