Where do we begin and what big changes can we make?

Alex Steffen: Build. That is at the top of the list.

We have a massive housing crisis here in the state in almost every city. We know that adding dense affordable green housing to cities is possible. And if we do it right, we can decrease auto dependence. We can drop emissions. And we can have the money to build the kinds of systems we are going to need to not only bring our CO2 down with clean energy, but also prepare for the very serious consequences that are already hitting our shores.

Richard Kennedy, landscape architect; senior principal, James Corner Field Operations

I am absolutely an optimist about the pressures and challenges ahead. I think cities are where the action is, but they are also the most sustainable way of living. They’re compact and dense and tied to transit. But cities can be better. They can be healthier, they can be greener, and they can be more equitable.

I think we all in some sense like being surrounded by people, being cheek to jowl with others. We go to popular restaurants and we come to events like this filled with people.

And so the solution is to actually make these housing projects and new development more compact, more dense, and to create more space that can be retained as nature, as green space, parks, trails, running spaces, playgrounds. And when the tides come in, these places get flooded. When storms come and rainwater comes from the hills, they get flooded. But when those storms stop and the tides recede, those places dry up.

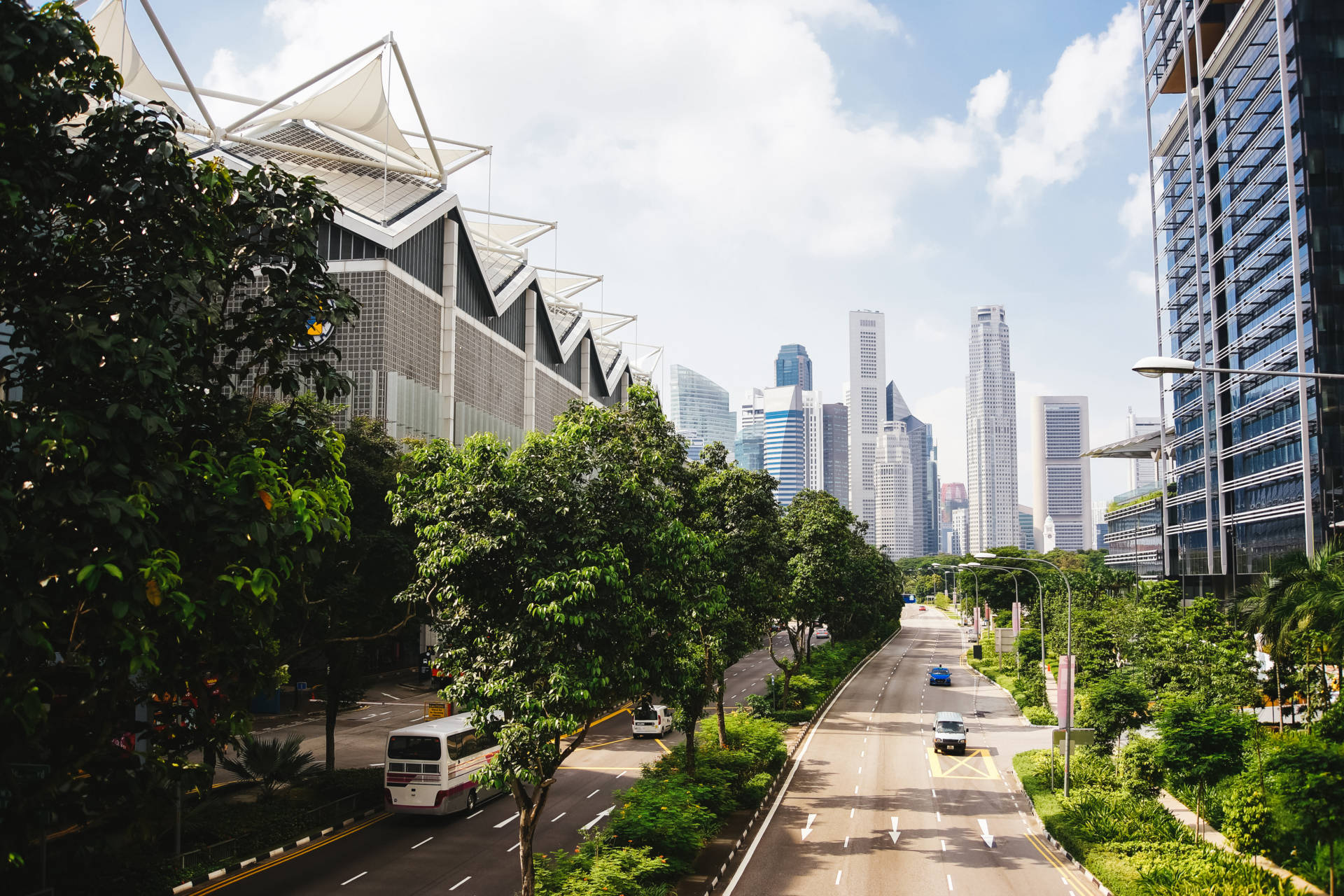

So it’s just more dense but at the same time more green and I think more vibrant. It’s doing it in a way where you’re identifying where there’s space for green resources and where there’s space for development.

And we do need to build. We do need to be creating those spaces where cities can grow and populations can live.

Annalee Newitz, author, “Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction; founder of io9

I think right now in the United States we have a model where most of our food is imported from another place. In San Franisco, we do have a whole locavore culture, which is kind of boutique food that’s grown locally, but most people get food that’s trucked or shipped in.

A lot of arguments have been made that if we want to reduce our carbon footprint, one way to do that is to try to have not necessarily farming on your roof, but farms located near the city. That would make the city or a set of cities able to sustain themselves within a local region.

And so you aren’t depending on truck routes, for example, to get your tomatoes or to get your oranges or to get your grapes. I don’t think we’re ever going to have a moment, at least in our lifetimes, where everyone in San Francisco is eating food only grown locally, but I think that that’s what we have to work toward.

It’s not just a technology problem; it’s also a ‘people problem‘

Liz Ogbu, designer, urbanist; founder and princicpal, Studio O

From an architecture perspective, we actually have the capacity to build better. We have made lots of advances in technology, and our buildings have a possibility of being carbon neutral.

The buildings that we design today make a much lighter footprint on the Earth than the ones from many years ago. In Silicon Valley we can talk about what it might look like to have a city without cars. That is all within our grasp. I think the challenge, however, is that it is not just a technology problem; it’s also a people problem.

So as an architect I can tell you the things designed to make that better city. But the other piece of it is: What are the things that keep people poor? What are the things that keep us leading a wasteful existence? Are we at the point where we’re ready to make those big sacrifices?

Right now most of us with privilege are causing harm for those who are without. So what are we willing to give up? What are we willing to spend more on, in terms of taxes or in terms of us completely re-configuring the ways in which we design our cities. Maybe it’s not having such huge sprawl. Maybe our cities need to be much more compact and we have to be willing to let go of having such a large footprint. We could have lots of green life all around. We can have no cars on this street.

The way that we’re going, those who have already benefited from the system the way it is now will probably be the ones who continue to benefit, and the poor will continue to remain poor unless we do something about changing our social systems. I think the city of the future may have Jetsons-like scenery, but you’re probably still going to have some homeless people on the street.

Annalee Newitz: I think borders are the enemy of survival. And I mean that in many different ways. But I think that we are looking toward a future where there is going to be mass migration due to climate change and political instability. We’re going to have to be thinking about more than the questions around developing more places for them to live, which I think absolutely we do.

So what could the city of the future look like?

Annalee Newitz: A lot of designers now are thinking about incorporating biological materials into city design. There’s a really interesting group in New York called The Living, and they’re working on the idea that maybe one day you would plant a seed and grow a house.

That’s a kind of extreme version of what they’re working on. But the idea would be that you might be able to build with living materials with semipermeable membranes and self-healing materials so that you wouldn’t have to just rip down your house and build a new one. It could work with the environment instead of against the environment. And I think that stuff is quite exciting.

I love the idea of a city which itself is alive, and also a city that maybe is built to contain nonhuman animals. We do live with animals all the time, but we don’t build our cities in harmony with them. I love the notion of a city that might build a migration pathway for animals to pass through because this is a huge issue in cities often, where we kind of wreck natural habitats and the natural pathways of the other animals that want to get through.

Learning from the past

Annalee Newitz: The past several years I’ve been visiting archaeological sites and talking with folks who work on ancient urban sites where people left. I looked at four cities in particular — Pompeii was one of them. And you think you know why people left Pompeii. But actually it’s more complicated than that.

What really united all of these cities, one of which is 9,000 years old, is that people would start to leave those cities. They abandoned city life, often at great expense and personal cost, when there were environmental problems and infrastructure problems combined with political problems. And that’s pretty much the recipe for wrecking a city, when you combine those two things.

A lot of cities survive massive environmental problems, infrastructure that’s crumbling, if they have a healthy political or community structure. For example, Rome has survived thousands of years of political instability. But they have managed to maintain a healthy infrastructure through that time. So really what I found was that climate change and infrastructure maintenance are a huge theme throughout the history of cities.

I think what history shows us is that as we look to the future we constantly have to weigh both the nuts and bolts of environmental sustainability and the more heady work of thinking through our political system and thinking through how we handle the most vulnerable people in our society.

Start Locally

Liz Ogbu: It’s been very interesting since this current administration came into power how all of a sudden you saw action happening at the city and at the state level. People stopped expecting the federal government to do stuff for us, and we started to invest more in our local systems and talk about how we can make change at that level. We need to double down on that.

If you try to think about all of this stuff at the federal level, it’s almost too overwhelming. We just stop because it’s like there’s nothing we can do about that. Whereas at the local level we actually do have the capacity to start to make a change. And so if we start to talk about not just what are we passing but what are we doing to actually heal the social structures at the local level, we actually might have a chance of eventually making our way up to completely redoing what’s coming from the federal level.