On a warm summer day the lines for ice cream at the Daily Scoop on the University of Wisconsin- Madison campus are frustratingly long. Everyone is herded together, waiting their turn to order a cone filled with creamy, cold ice cream -- anything to take the edge off that overheated feeling. But securing a steady supply of this refreshing treat depends on keeping cows cool, too.

Cows create a lot of body heat and use a large amount of energy in the process of producing milk. “When you are comfortable, a cow is warm; when you are hot, a cow is miserable; and when you are cold, a cow is probably fine,” explained Dr. Lou Armentano, a professor in the Department of Dairy Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. On those hot summer days, cows immediately respond to the high temperature with decreased milk production.

Cows produce the most milk and are most comfortable when the temperature is between 15 and 85 degrees Fahrenheit. When the temperature increases to the 85- to 105-degree range, milk production is decreased by 20 percent, or more. Once it gets above 105 degrees it can be fatal. At that point, up to 5 percent of the herd can be expected to die.

“The big issue for all the farmers we work with is risk. Extreme weather is adding uncertainty to this already uncertain profession,” according to Michelle Miller, associate director of the UW-Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems.

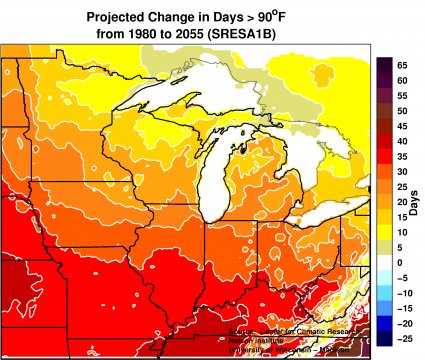

In an average year Madison would expect 13 days above 90 degrees, but in the summer of 2012 there were 39 days when the temperature surpassed that mark. And scientists expect more hot summers like that in the future.

The Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts (WICCI) predicts that summer days and nights in Wisconsin will become increasingly warmer. Climate models point toward an average temperature increase of as much as 3 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit in Wisconsin by mid-century. By 2055 Madison may be seeing an average of 37 days above 90 degrees and 4 above 100 degrees. Many cows are confined to barns with some measure of temperature control, so for them, extreme weather is not a major concern.

Various techniques are used in the barns to keep the cows cool. Open-stall barns have curtains that can be opened in the summer to allow natural breezes to blow through. Temperatures can also be held at bay by building the barn so that it’s in the shade during the hottest part of the day. And some farms have installed evaporating systems that mist and fan the cows on hot days.