Big construction projects are rarely straightforward. The new San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge is a prime example, thanks to unexpected problems with the steel. But there, at least, nature was not to blame. This week a long-running dam project made the news when a geological discovery forced the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission to move millions of dollars around and push back its schedule by three years. Big excavations are like exploratory surgery, no matter how carefully planned, because mapping the underground is never certain.

The Calaveras Reservoir dam, east of Milpitas, is a massive earthen structure built across Calaveras Creek in 1925. These traditional dam designs are generally robust—the Crystal Springs Reservoir on the Peninsula has one that easily weathered the 1906 earthquake while the fault moved beneath it. However, the Calaveras Dam needed more work. The reservoir needs to be a reliable six-month backup water supply in case the Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct is out of action. And what could damage the aqueduct? Among other things, a major earthquake on the Calaveras fault, which happens to run right under the Calaveras Reservoir next to the dam.

The plan for meeting this dire scenario was to build a new dam just downstream of the old one. It will use the existing hills on either side of the creek as buttresses and be largely made of the rock excavated from the hills. The work was proceeding without incident until June of last year when excavators on the western buttress found signs of a huge, ancient landslide in the Temblor Formation.

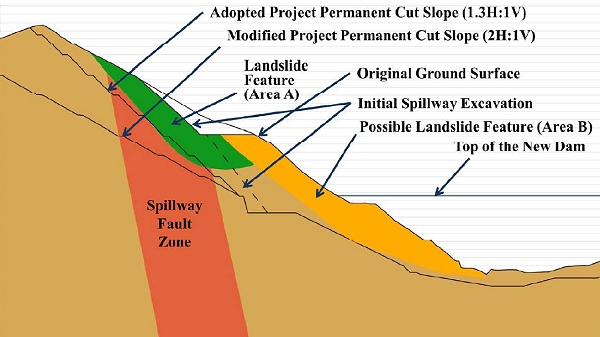

Cutting into the hillslope under those circumstances would risk reactivating the slide, which could endanger the workers and threaten the new dam ever afterward. So now they will cut deeper to create a shallower slope, producing about a million and a half cubic yards of extra rubble and pushing the construction schedule back three years.

Here's a view of the project as seen looking south from Sunol Regional Wilderness in July 2012. The reservoir, its water level drawn down for safety reasons, is just visible between the two cuts making up the buttresses for the new dam. The cut on the left (the right bank of Calaveras Creek) is in bluish metamorphic rock of the Franciscan Complex, and the cut on the right is in the much younger brown sandstone of the Temblor Formation. (The chopped-up hill in the middle is downstream from the dam site; the creek runs around it on the left side.)

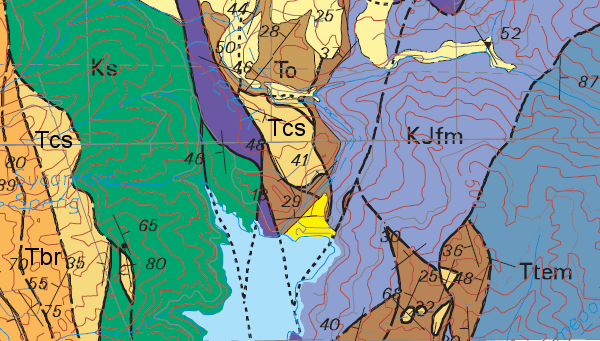

The landslide was discovered in the Temblor Formation. Here's the part of the Alameda County geologic map that covers the area. The photo above was taken from roughly the "25" mark at the top of the map. The solid black lines running north-south down the middle are major strands of the Calaveras fault.

The amended dam plan, filed with the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission last December, shows an east-west cross section of the dam site. The extra digging will happen on the left side to create a slope that is less steep and more stable.

I have to say a little about the Temblor Formation, which occurs mostly in the southern Central Valley beneath the Monterey Formation. It gets its name from the Temblor Range, where its type section was described. And the Temblor Range got its name after the great 1857 earthquake ripped through the area. It's a coarse-grained marine sandstone full of fossils, and this spot appears to be its northernmost outcrop—right next to another earthquake fault.