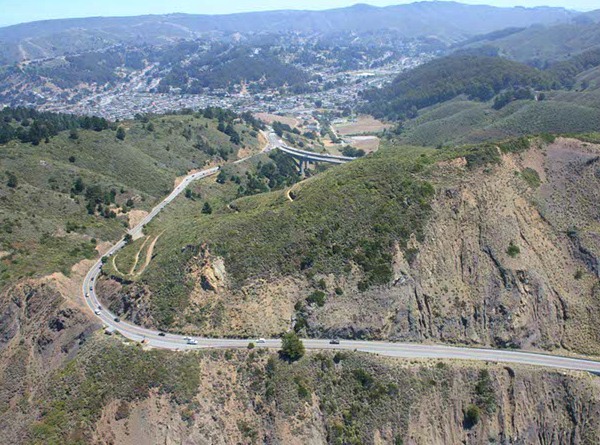

With the opening of the Lantos Tunnel this week at the notorious Devil's Slide on state Route 1, the work is not finished. The winding, vertiginous old road and the 70 acres of land it sits on will be handed over to San Mateo County, which has pledged to give it a makeover and splice it into the California Coastal Trail, adding a new attraction to the Devil's Slide Coast. The facilities will include parking lots at each end, water, bathrooms, trash bins, rails and pedestrian crossings.

Hikers and bicyclists will be thrilled with the high views up and down the coast. They may feel a tickle as they look at the surf hundreds of feet below. And some of them will feel curiosity as they look inland at the sides of the road, about 1.3 miles of it, that they could never stop and see before.

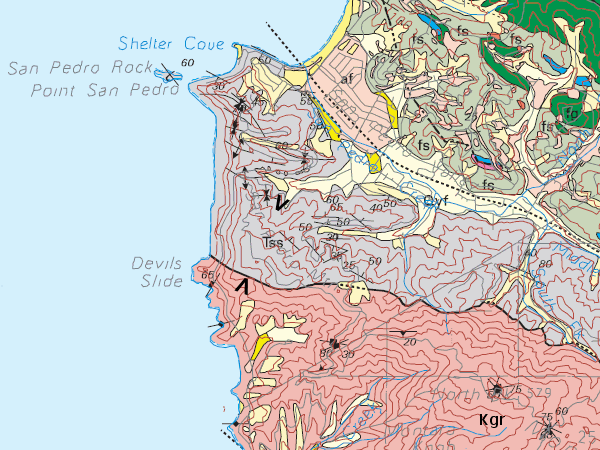

This stretch of road passes through two very different sets of rocks. The south end is the granite of Montara Mountain; I showed you some of this at Quarry Park in El Granada, a bit farther south, in 2011. It holds up the rugged headlands around the tunnel's mouth. It dates from Cretaceous time, just like the granite in the Sierra Nevada—and in fact it's the same stuff, ripped out of the range and pulled northward here by the San Andreas fault. The same granite is found as far north as Bodega Head and south to San Luis Obispo County (including Pinnacles and Fremont Peak, part of a sliver of tectonic plate that geologists know as the Salinian block.

The north end is a thick pile of mudstone that dates from Paleocene time, slightly younger than the granite. This is the material that gave Devil's Slide its name. It's been falling into the sea for untold centuries, including the last century in which we have been vainly putting roads across the cliffs.

The San Mateo County geologic map describes it as marine shale and sandstone with beds of conglomerate. The conglomerate is basically sandstone that includes "angular boulders of granitic rock as long as 2 meters and smaller boulders, cobbles, and rounded pebbles of hornblende gneiss, muscovite gneiss and schist, Franciscan chert, quartzite, limestone, sandstone, and shale." That variety of material represents a long-vanished countryside rather like today's, with vigorous rivers that carried this coarse sedimentary material straight out to sea.