But I was feeling pretty pleased with myself when I spread my hands out in front of Carol Matthews. She’s a psychiatrist at the University of California San Francisco.

"Pathological Grooming"

“Well, I can see you’re a nail biter,” she told me. Your cuticles are pushed back and you have the bumpiness you see with chronic nail biters. But it’s not bad. It looks like you’re a recovered nail biter, is what I’d say.”

Matthews specializes in pathological grooming, a group of behaviors that includes nail biting, although nail biters rarely come in for treatment. She says the patients she sees the most are the trichotillomaniacs, people who pull their hair out.

“Trichotillomania is the most socially visible,” says Matthews. “It's much harder to hide the fact that you don't have eyebrows or that you have a big bald spot, so it’s much more distressing to people. Skin picking comes next.”

In a sense, these behaviors stem from a normal, evolutionarily adaptive behavior: grooming. But in pathological groomers, those behaviors go haywire. Instead of being triggered by, say, a hangnail, a pathological nail-biter will be triggered by all sorts of things: driving, reading a book, or feeling anxious.

From "Not-Otherwise Classified" to "Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum"

Until recently these pathological grooming behaviors were classified almost as an afterthought in the DSM: “Impulse-Control Disorders Not Otherwise Classified.”

But the new DSM, the DSM-5, proposes something different.

It creates a category called Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders that includes classic OCD behaviors, people who wash their hands compulsively or have to line up their shoes a certain way. The idea is to expand this group so that it includes not just OCD, but pathological grooming, as well as hoarding and several other disorders.

This does not mean that insurance companies are going to raise premiums on nail biters, or issue policy-mandated manicures. (In fact nail biting, itself, isn’t even specifically mentioned in the DSM-5, because in the vast majority of cases, it’s not disabling enough to count as a “disorder.”)

But the new classification does give nail biters – and psychiatrists – another way to think about something that used to be considered simply a bad habit. And that raises some questions.

For one, says Mathews, “There’s always the worry of are we over-pathologizing normal behaviors. That’s always a worry with the DSM.”

And does this grouping make sense?

Nail biting? It's a little bit fun.

After all, there are real differences between OCD and those of us who pick, pull, or bite, including one big one.

“In OCD,” says Matthews, “the compulsion is really unwanted.”

People with OCD don’t want to be washing their hands, or checking the stove over and over again, she says. They’re terrified that if they don’t do it, something bad will happen.

But the biters hair pullers and skin pickers? They tell a different story. Matthews says she hears this from her pathological groomers all the time: They enjoy it.

“It's rewarding. It feels good,” she says. “When you get the right nail, it feels good. It’s kind of a funny sense of reward, but it’s a reward.”

Another consideration for the drafters of the DSM-5, when cataloguing all these disorders, is genetics. Are there genetic signatures that help explain both OCD and pathological grooming? Do the two behaviors share any genetic markers? And to what extent are these behaviors hereditary?

Meet the OCD mouse

Francis Lee is a neuroscientist at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. He studies mice.

A few years ago, a colleague – another mouse guy -- came to Lee with a mystery: a mouse, bred with a specific gene mutation, that was behaving very oddly.

“I was dumbstruck,” he says.

The mouse was doing something Lee instantly recognized from his work as a psychiatrist, studying people.

“It was hunched over,” Lee says, “repetitively moving its front paws over its eyes and ears.”

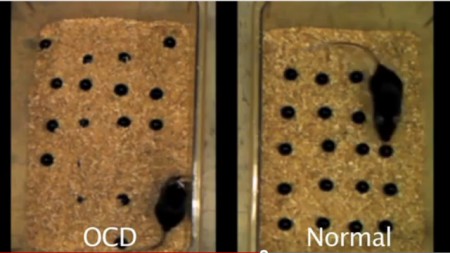

In mice, as in many animals, such grooming behaviors are normal and healthy. But these mice were doing it at a completely different scale. Whereas normal mice might groom themselves for a couple of seconds, mice with this genetic mutation – the Slitrk5 deficiency – groom in bursts of 30 seconds or longer, then start all over again just seconds later.

In fact, the mice groom so much, they give themselves bald spots.

“They remove the hair from around their eyes. They actually look like they have little white rings around their eyes,” says Lee

To Lee, who published this work in Nature Medicine in 2010, this mouse-brand of pathological grooming looks like OCD: a repetitive behavior that the mice are compelled to do. And just like people with OCD, these mice, he says, often exhibit high levels of anxiety and fearfulness. In fact, they’re some of the most fearful, risk-averse mice he’s ever seen.

Lee’s work shows that in mice, a single gene tweak can cause OCD-like symptoms, including over-grooming. Now, scientists are trying to find out whether the same mutations might contribute to OCD, or pathological-grooming, in people.

The (bitten) apple never falls far from the tree

Which brings me to the reason that I finally quit. My daughter Cora, age 3, recently started biting her own nails.

When I asked her about it, she explained, “I don’t want to put my fingers in my mouth. I just do it even though I don’t want to.”

I felt terrible about this. Either I’d waited too long to stop biting my nails and Cora had learned from watching me -- the same way I had, with my own mother -- or I'd passed on some pathological grooming gene that had her doomed from the start.

Worse, I was making her feel bad about it.

“I’m gonna stop doing it,” she told me. “Why?” I asked. “Because you don’t like me to, remember?" she replied.

In many ways, these questions the DSM is grappling with are the same ones we parents have about our kids. Are our genes their destiny? What’s a bad habit, and what’s a pathology?