Clad in a bright yellow raincoat and a crown of butterflies, laughing and singing, Ariel delighted the audience from the first moments of California Shakespeare Theater's "The Tempest."

I always love productions at the open-air Bruns Memorial Theater, but the airy sprites of Shakespeare's last full play seem particularly well-suited to the natural environment. Orinda's eucalyptus groves and rolling golden hills could as easily populate Prospero's remote island as do the characters of kings and dukes, clowns and cannibals.

Of all the characters, though, Ariel was "an easy favorite" in the words of my father-in-law. Played by choreographer Erika Chong Shuch, her movements overflowed with emotion and expression. It was easy to believe in her magic.

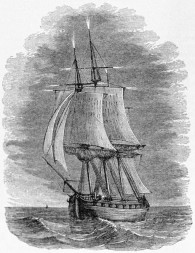

I boarded the king's ship; now on the beak,

Now in the waist, the deck, in every cabin,

I flamed amazement: sometime I'd divide,

And burn in many places; on the topmast,

The yards and bowsprit, would I flame distinctly,

Then meet and join.

--Ariel, The Tempest (Act I, Scene 2), William Shakespeare