Our scientific monitoring of the CA Least Tern nesting colony turned out to be more gripping than the best TV drama as we witnessed soaring action, villains and heroes, family ties, and death by predator all within the span of three hours. My husband and I took the training course offered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service a few weeks ago to learn the protocols and procedures for becoming volunteers for the predator monitoring program called "Tern Watch." Father’s Day evening was our first shift.

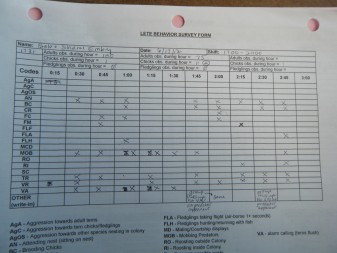

There was a little thrill of excitement as we entered through the locked gate and headed out to the observation area. Gusty winds and cool fog over the peninsula ridges across the bay greeted us. The colony of several hundred terns bustled with birds coming and going in the evening sun. Our job was to stay in our car "bird blind", note tern behavior every fifteen minutes and document any potential predator activity by other species: gulls, ravens, American kestrels and the dreaded burrowing owls and peregrine falcons.

It was hard to see terns on the ground as the adults blend in among the gravel and oyster shells on the flat nesting site. The chicks and fledglings are nearly impossible to see until they move. With our binoculars and spotting scope, we peered at and recorded life in the colony like visitors to a foreign world. Adults returned with small silver fish and fed them to other adults sitting on nests. Chicks sometimes chased down the adults in their anxiety for dinner. There was nearly constant calling of the birds like a murmur among neighbors.

That all changed after 45 minutes when nearly 100 terns rose out of the colony at once with a commotion of alarm calls. Scanning the sky, we spotted the culprit; a small hovering bird. The terns were a flurry of motion, diving from above, swooping past it on their thin, back-swept wings. The small raptor paused, moved, faked left and right, then after a few moments dropped down into the nesting colony. We struggled to keep it in sight and located it, still being dived upon by the adults. Clearly, it had gotten something: an unattended chick. The American kestrel proceeded to kill and consume it within the colony for some five minutes. Our adrenaline was up, and while we documented the occurrence and notified the staff, we couldn’t help but feel sorry for the terns who had lost one of their own.

The next hour passed with a few gulls flying over and a few terns chasing after them to keep them moving. Then another raptor made its appearance high above the colony, this time a Coopers hawk. The colony rallied and successfully chased it off. Then just after the terns calmed down, a kestrel returned. It swooped in after briefly hovering, landed and then flew low out of the colony. Its low flight made me suspect it had captured a chick. Once out of the colony, though, and with sunset approaching, the birds gave up the chase. The last of the evening found a few adults still flying in with food, as adults, juveniles and chicks snuggled down for the night under a sky blazing with lavender and orange sherbert clouds. Our work was done, too. I can't wait for our next shift, knowing our volunteer time is well spent helping in the important work of giving management data that will help save an endangered species.