I'm glad to see that Ben Burress, my colleague at KQED QUEST, was open to the thrill of deep time as he laid hands on some of California's oldest rock in Death Valley.

When I went to geology school, back in the ice ages, I brought with me the same normal, healthy fascination with extreme age—geological age. At that time there was still a great deal of mystery about the earliest times. To me, the most mysterious thing you could call a rock was "Precambrian," that is, rock dating from the time before the earliest hard fossils appeared, marking the base of the Cambrian Period. Precambrian time amounts to four billion years, nine-tenths of all Earth history. Unlike familiar, fossil-studded post-Precambrian time (I know that's a weird term: geologists call it the Phanerozoic Eon), the Precambrian was an endless succession of enigmatic, mashed-up rocks. Their story wasn't really a story but a pile of hints and fragments—mountain ranges rising and eroding, continents merging and separating, just one damn thing after (or before?) another in the dimness of deep time.

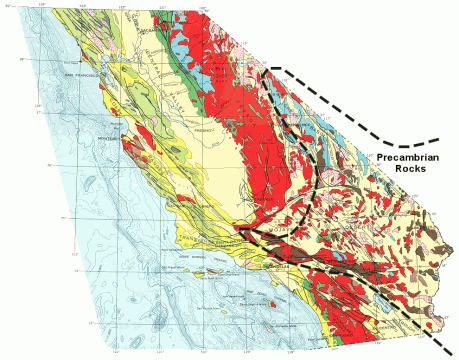

We have a better picture of the Precambrian now, but really, it's still pretty blurry. If you look at the geologic time scale, you'll see that the Precambrian time divisions are set at arbitrary even numbers of years, not significant geologic events. In California, our oldest rocks all originated around 1700 million years ago in the Paleoproterozoic Era, and they all sit in the corner of the state outlined on this geologic map.

The outline marks a segment of the North American continent's ancient foundation—the craton—called Mojavia for the Mojave Desert. It's a pretty young part of the craton, and it's all we've got.

The oldest basement rocks of Mojavia are all highly altered—squeezed and stretched rocks classified as gneiss or schist. And they're still on the move today as plate-tectonic interactions are both stretching western North America apart and, in California, yanking it northward along the San Andreas fault system. Just as Sierran granite (shown in red) has been pulled all the way up to the Bay Area, so has a big chunk of Mojavia making up the San Gabriel Mountains.