In the foothills due south of San Jose sit the remnants of California's first mining bonanza, the New Almaden mercury district. Today Almaden Quicksilver County Park is a rugged playground for hikers, bicyclists and equestrians, but lovers of geology and mines have a special kind of fun there.

The first Californians mined a deep-red ore they called mohetka in the heights of Los Capitancillos Ridge. Like other ancient peoples around the world, they used it as a pigment. In 1845 a Mexican visitor recognized the substance as cinnabar or mercury ore. Soon afterward the New World's richest quicksilver mining district began production, supplying the mercury for the refiners of the California Gold Rush. Its name, New Almaden, echoed the famous Almadén mines of Spain. A hundred years later, the mines had yielded mercury in the amount of more than a million flasks—a volume of the liquid metal weighing 76 pounds. Although mining ended in the 1970s, geologists believe that much undiscovered ore remains.

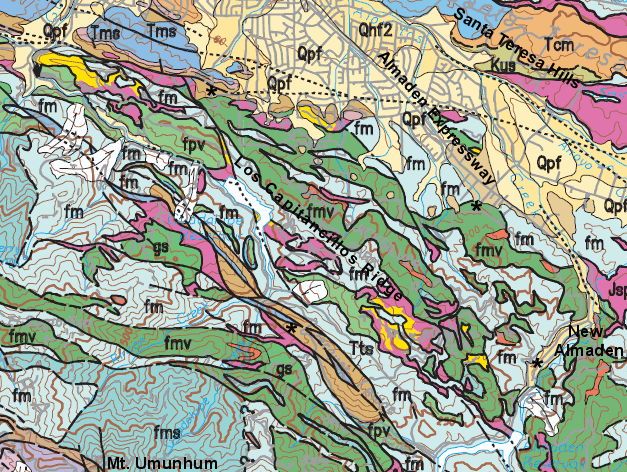

Let's look at the geologic map of the area (derived from USGS Map OF-98-975).

It's kind of a mess, and the details are in the caption, but basically Los Capitancillos Ridge is like many other Bay Area mercury sites, an intricate mixture of Franciscan rocks and serpentinite that has been kneaded and heated and injected with metal-bearing fluids. These fluids, derived from magma intrusions, replaced the minerals in the serpentinite and turned it into silica-carbonate rock. The cinnabar lodes, in turn, were emplaced in and near the silica-carbonates. As you hike about the ridge, keep an eye underfoot for the widespread serpentinite.

Among other things, the park contains mines and machinery spanning a century of progress from traditional techniques of medieval origin to modern American facilities. One mine entrance, the San Cristobal tunnel, has been kept open for a short distance.

Go on in and look for the veins in the walls. These are typically filled with quartz or dolomite.

Another worthwhile spot is the site of the Buena Vista shaft, the deepest in the district. The foundation of the pumphouse is constructed of large blocks of local sandstone and Sierran granite. It was abandoned in 1893.

Nearby are extensive piles of mine tailings. Although this shaft produced only minor amounts of ore, the rocks themselves are interesting. Remember that collecting rocks and minerals is forbidden. A ranger told me that if people kept taking things home with them, eventually there would be no tailings left. I don't see the problem with that, and if I could make the rules I would give rockhounds access to limited parts of the park.