Researchers are continuously looking through this genetic code to search for genes that may make us susceptible to a particular disease. Finding that needle in the haystack takes time, as scientists must look at each piece of data to evaluate its potential to wreak biological havoc. They also need context to understand the significance of each gene’s sequence.

“By themselves, sequences tell us nothing,” Waldispühl said. To make sense of this data, researchers are interested in comparing human DNA to that of other animals, like monkeys or mice. This gives us a window into evolution – if the exact same sequence ended up in horses and humans, then it is probably important, and a change, or mutation, would be bad news.

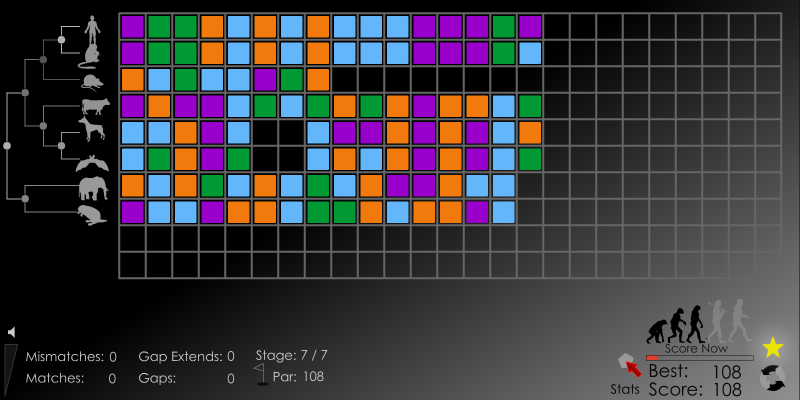

Waldispühl turned these inter-species comparisons into a game by color-coding the DNA and laying out human and animal sequences on top of each other, the way many scientists do to make sense of it.

“In the puzzle, you’re trying to make columns of the same color, [and] you’re finding evolutionarily conserved regions.”

The result is a game that looks something like a mash-up of Tetris and a Rubik’s cube. To play, you try to arrange the rows to get the same color going down across different species, and you can introduce gaps if necessary. The computer’s score is the ‘Par’, and your goal is to beat it.

Competing with the computer may sound daunting at first. After all, this process seems like something computers should be really good at. But for this kind of pattern recognition, humans turn out to be much smarter than computers at figuring out which mutations can be thrown away, and which may be a red flag for disease.

For all the nuances of the science behind the game, it should ultimately still be fun to play. I asked Jon Bernstein, a doctor and researcher at Stanford, to try it out. “I thought it was very interesting – it was visually appealing, the interface was nice, and fun to play around with.”

The game is focused on genetics, Dr. Bernstein’s area of expertise, but that didn’t mean it was easy. “Many of the levels were pretty challenging.”

The game is timely, as DNA sequencing is becoming more and more useful in terms of diagnosing and treating all sorts of illnesses

“There are many, many situations in which genetic information is helpful in understanding the cause of human disease,” said Bernstein. “There are many cases in which it impacts how you take care of people and the counseling you can provide them.”

But as Bernstein told me, some forms of sequencing are still very expensive, on the order of $10,000. “And most of the cost is really the interpretation, not running the test itself.”

Games like Phylo are an effort to help scientists interpret these data. By making these problems fun, easy to play with, and accessible to anyone in the world, game designers like Waldispühl are essentially crowd-sourcing solutions to complex problems in health.

And there are plenty of gamers who would be willing to help out. Waldispühl told me that McGill put out a press release on the game and got a much larger response than they expected.

“A couple of hours after we launched the game, the server was saturated and we put all of the department in an emergency state because everything was blocked,” he said.

“We had basically a puzzle downloaded every half-second. It was just crazy.”

Finding innovative ways to quickly make sense of genetic data is becoming more important as sequencing becomes faster and more widely used. However, there are many questions that come up between sequencing a person’s DNA and pinpointing the cause of their disease, and Phylo may be answering the wrong one.

“This particular game is about aligning DNA sequences. In clinical medicine, a lot of questions are asked and answered at the level of protein,” Stanford’s Bernstein said.

DNA is the blueprint for protein, and bad proteins can cause disease. Looking at information from the protein perspective would be much more useful to doctors, and games like Foldit are already looking at some aspects of that problem.

Foldit is a science-focused game that was first released to the public in 2008, and it has had considerable success since then. It allows players to virtually interact with proteins and solve puzzles about their shape. Foldit was able to harness the power of the game-playing masses to determine the shape of the AIDS virus in rhesus monkeys, a problem that had eluded researchers for 15 years. They even published their findings in a sub-journal of Nature.

Phylo may not be as useful as Foldit in its current incarnation, but it does have potential. Since its launch in November 2010, Phylo has contributed to 450,000 solutions through the work of 20,000 registered players and thousands more who play anonymously. Its interface could easily be adopted to compare proteins instead of DNA sequences, but the challenge would be in making it enjoyable for anyone to play.

Photo courtesy of Official GDC

Photo courtesy of Official GDC