Ten percent may seem like a small number, but it’s enough to “put a school at risk of an outbreak of a vaccine-preventable disease if the disease was introduced,” said Dr. Robert Schechter, chief of the immunization branch of the state Department of Public Health, located in Richmond.

The issue is of increasing concern to medical leaders in California, where a whooping cough outbreak this year has made more than 5,000 people sick and resulted in the deaths of nine babies.

“Increases in the numbers of children whose parents choose not to immunize them are concerning,” said Kathleen Harriman, an epidemiologist with the department’s immunization branch. “In Europe, it was a drop in childhood immunization rates that allowed previously controlled diseases to become endemic again.”

Officials strive to keep immunization rates high enough to confer “herd immunity,” or “community immunity,” to the population. Herd immunity occurs when the vaccination of a portion of the population provides protection to unvaccinated people.

Depending on the disease and the community in which it might occur, in order for unvaccinated people to be protected against communicable diseases, approximately 75 to 95 percent of the population has to be vaccinated against them, medical experts say.

“For example, the level of vaccine coverage necessary to retain herd immunity to measles, a vaccine preventable disease that has recently caused outbreaks in schools, is estimated to be 83 percent to 94 percent,” said Schechter.

The 20 states that appear in green - California among them - allow parents to get a personal belief exemption for their child. The states highlighted in pink allow parents to opt out of vaccination only for religious reasons. (Credit: Institute for Vaccine Safety, Johns Hopkins University). Enlarge this map.

The 20 states that appear in green - California among them - allow parents to get a personal belief exemption for their child. The states highlighted in pink allow parents to opt out of vaccination only for religious reasons. (Credit: Institute for Vaccine Safety, Johns Hopkins University). Enlarge this map.

California is one of 20 states that allow parents to opt out from providing proof that their children have received mandatory vaccinations by stating that they are philosophically opposed to their child being vaccinated.

All states except for Mississippi and West Virginia allow parents to opt out because of their religious beliefs. And every state allows for children who have a medical reason to opt out.

In California, children starting kindergarten must show proof that they have had five doses of the whooping cough vaccine, four of the polio, three of the hepatitis B, two of the combined measles-mumps-rubella and one of the chickenpox vaccine, or that they have been sick with the chickenpox instead.

California’s vaccine exemption system is among the easiest in the country, said Dr. Saad Omer, of the Emory Vaccine Center at Emory University in Atlanta, who has compared exemptions around the country. California law requires only that a parent sign a form called a personal belief affidavit – also known as a personal belief exemption – stating that immunizations are contrary to his or her beliefs.

In total, 10,280 kindergartners in California had personal belief exemptions in 2009. That’s 2 percent of all the state’s kindergartners.

Omer found that in states where getting an exemption is easy, such as in California, the rate of whooping cough was at least 50 percent higher than in states that made it more difficult for parents to opt out.

“It’s not just an abstract legal requirement,” Omer said. “It has an impact on disease rates.”

California is in the midst of a whooping cough epidemic that has made roughly 5,300 people sick in 2010 – the most cases reported in 60 years. Nine people have died, all of them babies. Eight of them were under two months of age, too young to be vaccinated against the disease. The ninth baby had received the first dose of the vaccine two weeks before getting sick, according to the California Department of Public Health.

Whooping cough is the common name for pertussis, a bacterial respiratory infection that causes a persistent, fitful cough that can be life-threatening for infants. Highly infectious, it gets its name from the characteristic “whoop” sound that happens as people gasp for breath, although many babies under six months of age don’t develop the whoop.

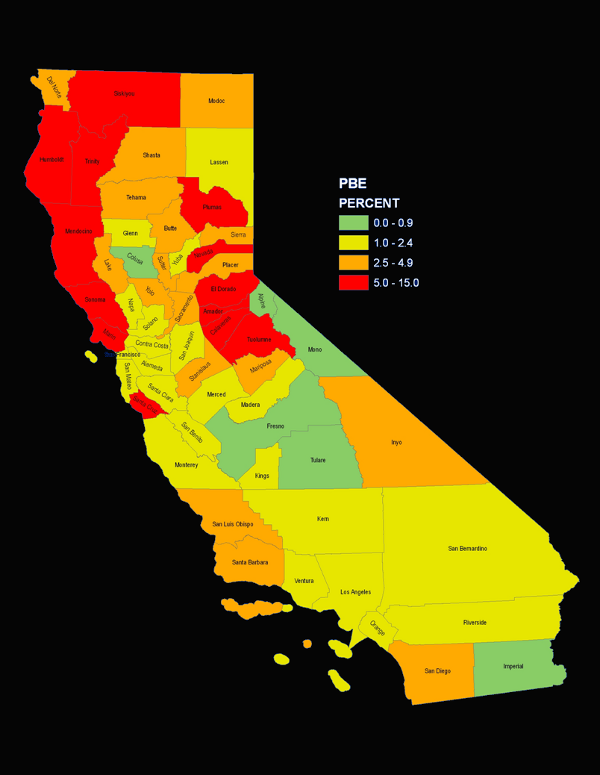

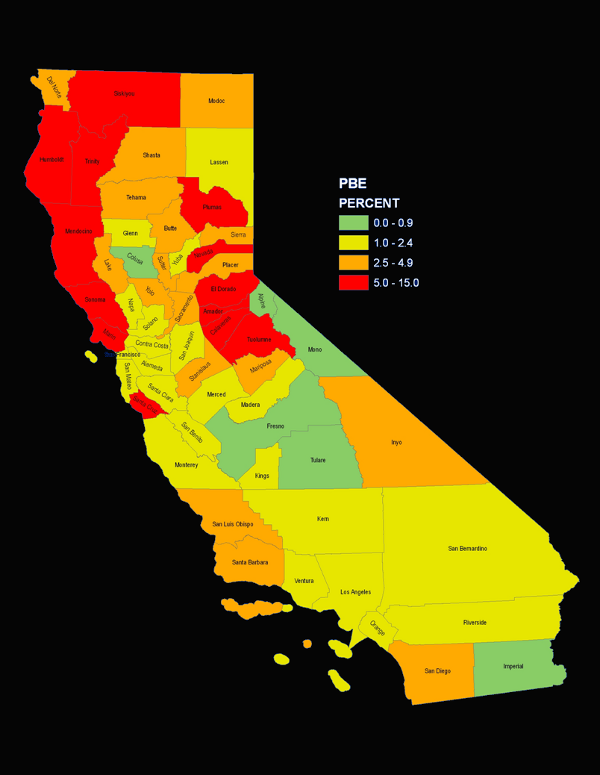

In California, some counties where the rates of personal exemptions are high have suffered more cases of whooping cough. In Marin, for example, 7 percent of kindergarten students had personal exemptions – the highest rate in the Bay Area. The county has been particularly hard hit by whooping cough, with more than 300 cases so far this year. But other counties that have been hard hit by the disease, such as the Central California county of Madera, don’t have particularly high rates of vaccine exemptions, said Catherine Martin, executive director of the California Immunization Coalition, a non-profit group in Sacramento.

This map shows the rate of personal belief exemptions in California counties in 2009. (Credit: California Department of Public Health) Enlarge this map.

This map shows the rate of personal belief exemptions in California counties in 2009. (Credit: California Department of Public Health) Enlarge this map.

In Marin, two private schools have the county’s highest rates of personal belief exemptions. At the Marin Waldorf School, in San Rafael, 31 of the 49 kindergartners had personal belief exemptions in 2009, a rate of 63 percent. So did eight of the 19 kindergartners at Mill Valley’s Greenwood School.

Among Marin’s public school districts, the two schools with the largest number of kindergartners with personal belief exemptions are in the Ross Valley School District. At Brookside Elementary, 15 out of 126 kindergartners have exemptions this year, a rate of 12 percent, and at Manor Elementary, 16 kindergartners – or 25 percent of the school’s 58 kindergartners – have exemptions.

“I think it is very easy for parents to sign the waiver,” said the school district’s nurse, Laurel Yrun.

As for why Marin County parents seem more likely to sign a waiver than parents in other California counties, she said, “It’s a good question. We’re a wealthy county; this is a community of fairly well-educated people, probably with good access to medical care. It’s interesting. I don’t know.”

Yrun said most of the parents who are signing exemptions in her district are doing so because they have opted not to give their children a particular vaccine. Only a minority of parents are opting out of vaccines altogether, she said. The most popular vaccine to skip in her district is the hepatitis B, followed by polio and the measles-mumps-rubella, she said. The whooping cough vaccine was the least likely to be skipped in her district, she said.

Nonetheless, the district was hard hit by whooping cough during the past school year. In Marin, only 87 percent of kindergartners had been vaccinated against whooping cough in 2009, compared to 93 percent statewide.

The California Department of Public Health hasn’t studied the characteristics of the parents who obtain exemptions. But research by Omer and his colleagues in Colorado, Massachusetts, Missouri and Washington confirms Yrun’s experience. They found that only 25 percent of exempted children didn’t receive any vaccines at all.

In the case of whooping cough, other factors in addition to personal belief exemptions have contributed to the epidemic in California, said Martin, of the California Immunization Coalition. For example, immunity to the bacterium that causes the disease wanes over time, so a large number of teenagers and adults are currently unprotected.

A whooping cough booster shot will become mandatory for middle schoolers in July 2011. (Credit: Gabriela Quiros)

A whooping cough booster shot will become mandatory for middle schoolers in July 2011. (Credit: Gabriela Quiros)

Children receive the fifth dose of the DTap vaccine that protects against whooping cough at age four or five. But by the time they’re 10 or 11, they need a booster shot called Tdap, which only became available in 2005. In September, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger signed into law an update to the health code that will require schools to check that children starting middle school have received the Tdap booster shot, starting in July of 2011.

Public health officials in the Bay Area have been concerned about the increase in the number of parents choosing to opt out of mandatory vaccinations since before this year’s whooping cough epidemic. They trace the change to what Emory University’s Omer refers to as “the Wakefield affair.”

In 1998, English doctor Andrew Wakefield published a study of 12 children linking the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine to autism. The paper caused rates of vaccination to fall and cases of measles to climb in the United Kingdom. Wakefield’s research has since been discredited. In February, the medical journal the Lancet retracted his paper, saying that its authors had made false claims about how the study was conducted.

Nonetheless, the paper’s effects are still being felt, said nurse Yrun.

“That’s been refuted, but once it’s been out in the media, parents hang onto it,” she said.

Concerns were also raised about thimerosal, a mercury derivative used as a preservative in some pediatric vaccines. It was eliminated in the United States from all but some flu vaccines in 2001. And numerous studies have found no connection between thimerosal and autism, the most recent of which was a Centers for Disease Control paper published in September.

“While we still need to find out the cause of autism, it seems quite clear that vaccinations are not one of them,” said Dr. Robert Benjamin, public health officer of Alameda County.

Benjamin is one of the public health officers who will be attending a meeting organized by the California Immunization Coalition in mid-November. The meeting will bring together a small group of private doctors, public health officials and representatives of medical associations interested in discussing possible changes to the personal belief exemptions, said the coalition’s Catherine Martin.

Benjamin said that in Alameda County, 11 percent of the people who have contracted pertussis had a personal belief exemption.

“While it doesn’t sound like a large percentage, it’s significant not only in that these kids are acquiring pertussis, but they’re also transmitting it,” he said. “This is where the personal belief exemption is an individual decision which has large societal and community ramifications.”

Benjamin said he would like to change the exemption’s wording so that it makes parents reflect on the impact their decision might have on the community. Or he would like to make it more difficult to obtain.

After studying personal belief exemptions around the country, Emory University’s Omer has come up with a guideline for those designing exemptions.

“It shouldn’t be easier to have your child exempted than to have your child immunized,” he said.

Omer has found that replacing a pre-printed form with a letter crafted by the parents in which they explain why they want the exemption could be an effective way to curtail the number of exemptions. Some states even require the letter to be notarized. A counseling session, viewing a video, or visiting the health department are some of the educational measures that have also been effective, he said. His team didn’t study the language of the exemptions in detail, he said. So he said he couldn’t comment on whether adding new wording to California’s form might help.

When the California group meets, the biggest challenge they might face is deciding who should be given the job of educating parents, if an educational component is agreed upon as the solution.

“To be honest, everybody is challenged budget-wise and everyone wants others to do the job,” said the immunization coalition’s Martin. “Some may feel it’s the schools’ job to educate the parents. Other people believe it’s the doctors’ and public health departments’ job. But the doctors and health departments are feeling stressed because of reimbursements and budgets.”

In fact, the state Legislature, facing record deficits, reduced the budget of the Department of Public Health’s infectious disease branch immunization program by $18 million last week, Martin said.

In Marin County, nurse Yrun said she’s curious to see how the efforts to change the exemptions system will pan out.

“It’s a huge issue to tackle,” she said. “Even though they’re a minority (parents who exempt their children), they have some pretty strong beliefs.”

But the whooping cough epidemic has raised concern among parents who are giving their children all their vaccines.

“Some people in the district were very angry,” she said. “We had parents calling and asking what the district was doing about the un-immunized children. I reassured them that the county is trying to reduce it. The public health department has gone out and had physicians talk to parents. But when you have events like that you usually have the people who believe in vaccinations who show up. The department has advertisements, they have a campaign – they’re using cows to depict herd immunity. It’s just now starting.”

To find out how many children might be under-vaccinated at your school, download the 2009 Immunization Status of Kindergarten Students in California (.pdf, 676 KB).

Watch our QUEST story about Northern California researchers searching for the causes of autism.

Public health officials in the Bay Area are concerned that not enough children are starting kindergarten with all their immunizations. (Credit: CDC/ Judy Schmidt)

Public health officials in the Bay Area are concerned that not enough children are starting kindergarten with all their immunizations. (Credit: CDC/ Judy Schmidt)