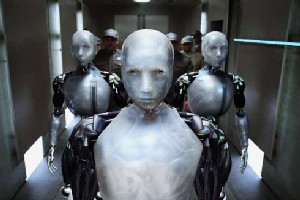

Robotic domination in I, Robot

Robotic domination in I, Robot

Ray Kurzweil's book The Singularity is Near is becoming something of a cult sensation. The 672-page paperback version of the book is ranked 1,494th on Amazon (on par with The Great Gatsby). Recently, Kurzweil announced a Google-backed Singularity University ($25,000 for a 9 week summer program; $12,000 for a 3 day "Executive Program"), lending a touch of academic rigor to an idea that has lived mostly in science fiction. For the time and budget conscious, a rash of Singularity-themed documentaries is now on the horizon.

The Singularity, as I understand it, is the point in time when computers will be smart enough to build even smarter computers, effectively removing humans from the design-build loop of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Kurzweil predicts 2050. That means I'll be 68 when the robots take over!

Predicting the future is no walk in the park, but when it comes to Artificial Intelligence, everyone's packing a lunch. So while I won't try to argue that Kurzweil is wrong (I think he is), it's good to place his predictions in the cultural history of wildly inaccurate AI speculation.

Consider these predictions, both made by outstanding computer scientists actively involved in AI research:

- 1965, Herbert Simon: "machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do."

- 1970, Marvin Minsky: "In from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being."

As it turned out, these claims were not even remotely true. In fact, the whole history of AI has been one of boom and bust cycles, the product of misplaced exuberant optimism.