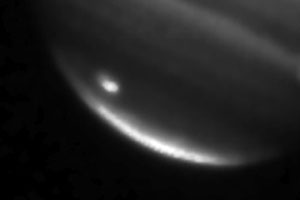

Hot spot created by impact on Jupiter, taken by NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii. Picture credit, NASA. An Earth-sized hole on Jupiter! the email alerts, websites, and finally news channels were saying on Monday, July 20th. At Chabot, we were polled by at least two local news channels asking what had happened. So, what happened?

Hot spot created by impact on Jupiter, taken by NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii. Picture credit, NASA. An Earth-sized hole on Jupiter! the email alerts, websites, and finally news channels were saying on Monday, July 20th. At Chabot, we were polled by at least two local news channels asking what had happened. So, what happened?

Evidently, the aftermath of some kind of collision on Jupiter was spotted by an amateur astronomer in Australia that Monday morning. He spotted a dark marking near the planet's South Pole, and alerted NASA. NASA in turn turned its large infrared telescope in Hawaii onto the scene of the crash.

There glowed the thermal footprint of the likely impact, the affected area roughly the size of the Earth. Had this impact taken place on Earth instead, the results would have been catastrophic. Fortunately this was Jupiter, half a billion miles away and large enough to absorb the impact without lasting effects. (And, owing to the fact that Jupiter is a gaseous planet with no solid surface, it would quickly heal from the trauma, not unlike that liquid-metal Terminator from the second movie of the same name.)

A significant event? Yes, in fact. But that's not all...

Rewind 15 years to July 20th, 1994, the middle of the week during which twenty-something fragments of the broken comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 were in fact colliding with Jupiter... An amazing coincidence? Yes; the two events likely have nothing to do with each other. So, then, a common event, if we're seeing two of them in the span of only 15 years? Well... not really.