Updated: On March 11, 2011, a massive 8.8 magnitude earthquake hit the Pacific Ocean nearby Northeastern Japan. The quake, and a tsunami that followed, caused massive damage and loss of life. The news put quake prone California on alert. While many of us would rather not think about the possibility of another major quake, we are surrounded by active faults. One East Bay fault has scientists especially concerned.

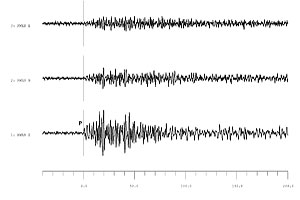

It's been called the most dangerous fault in the U.S. The Hayward Fault runs 40 miles, from San Pablo Bay to Fremont, through some of the most densely populated areas in the country. Every 140 years for the past two thousand the Hayward Fault has jolted the East Bay. Geologists have figured out the regular history of these quakes by carbon dating trenches along the fault. A lesser known cousin of the San Andreas the Hayward fault is a creeper. Basically, it moves, slowly, along the surface but deep inside... it's locked until tension builds up and and it slips. It appears that it is time for the fault to slip again. The last major earthquake on the Hayward fault was 1868. Scientists believe that the temblor registered 7.0 in magnitude. Hayward and San Leandro were devastated. But if the quake were to happen today, it would be a much different story.

I met Mary Lou Zoback out at the Fremont Bart station, which sits right on top of the Hayward Fault. She pointed out cracks in the parking lot from the creeping fault. Zoback is a geophysicist who worked 28 years at the U.S. Geological Survey and who has done catastrophe modeling of risky residential buildings. Her company estimates that a 6.8 quake, or bigger, on the Hayward Fault could cause a disaster on par with Hurricane Katrina, causing 168 billion dollars in damage and leaving at least 200,000 homeless.

A number of public buildings in the east bay are undergoing retrofitting to make them more structurally sound. Area hospitals have until 2013 to meet seismic safety standards. There is a state inventory of public schools prone to collapse in a major quake, but no such list exists for private schools. And retrofitting standards for risky residences are confusing. I talked with Jim Cook, of Bay Area Retrofit. He says existing codes are unclear and there really is no specific licensing for seismic home retrofitters. Cook has been fighting local governments for years to improve seismic safety standards.