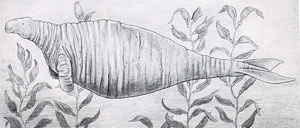

Drawing of a Steller's Sea Cow

Drawing of a Steller's Sea Cow

circa mid 18th centuryWhen we think about kelp forests, we envision froclicking sea otters, kelp fronds, sea urchins and a suite of other nearshore marine organisms. And, until a few hundred years ago, a 30 foot-long dugong.

This isn't a joke: Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) was a North Pacific relative of the South Pacific dugong, which are related to manatees (manatees and dugongs, in turns, are called sirenians), and once lived along the Pacific rim from California to Japan.

Hydrodamalis was more rotund than other sirenians; it had a notched fluke like other dugongs, thick elephantine skin, and it lacked fingers bones in front arms and instead had a boxing glove-shaped knob. What we know about Hydrodamalis is based solely on the account of one man, Georg Wilhelm Steller, a German naturalist, whose name has also been bestowed on jays, sea lions, and cormorants and other organisms. Steller served as ship's naturalist on Vitus Bering's Second Kamchatka Expedition in the mid 18th century. While returning from the Alaskan coast, in 1741, the crew shipwrecked on what is now known at Bering Island. Sick with scurvy, Bering died there, and while the crew overwintered waiting to be rescued, Steller documented the flora and fauna of the island, which included Hydrodamalis. Steller later died on the expedition, but his journal and descriptions returned to St. Petersburg, became published. Unfortunately, word of a tame, floating, giant mammal that could sustain several dozen sailors spread fast, and by 1768, less than 30 years after it was first discovered by Westerners, Russian fur-traders ate Hydrodamalis into extinction.

From Steller's account, we can glean key pieces of information that suggest that Hydrodamalis was in fact an important member of the kelp forest community, just like sea otters and sea urchins. Skulls and skeletal material belonging to Hydrodamalis has been found in Pleistocene deposits from Monterey Bay to Japan, which also hints at the antiquity of Hydrodamalis in these communities. The emerging picture is that the westward Aleutian Islands were likely the last refuge for the sea cow, having been hunted by coastal indigenous populations and successively exterminated throughout its range. It's not clear if human hunting is totally to blame: population sizes may never has been terribly large, and we don't really know how changes in climate might have affected Hydrodamalis.

Hydrodamalis reminds us that our picture of marine biodiversity is a fundamentally biased one: what we imagine to be "natural" in nearshore communities is really based at the scale of a human lifetime. All modern marine communities evolved prior to human presence, and, as many have shown through midden records or ships journals, wherever humans have lived, they have altered community composition. Daniel Pauly, of the University of British Columbia, calls this situation a shifting baseline: our perception of what's natural in marine communities is constantly being compared to population sizes that have long suffered at the hands of human-mediated depletion. These considerations are critical for conservation: we need to have a solid understanding of what was once "out there" if we want to any hope of saving the here and now.

![]() Nick Pyenson is a PhD candidate at the University of California, Berkeley, in the department of integrative biology and the museum of paleontology.

Nick Pyenson is a PhD candidate at the University of California, Berkeley, in the department of integrative biology and the museum of paleontology.