I’ve read all I can about how my neurons, attention span and social skills are all doomed by my technology-laden existence. I’ve started to bore myself with my bi-monthly existential crises about it all. It seems high time to find other ways to reflect on this strange new life we're living. Enter the weird, elegant, unsettling vision of the future that Spike Jonze has imagined for us in his new film Her, a place where the interpersonal dynamic with technology has shifted from addiction to love story. Her seems so well-timed, but not because it’s about a man falling in love with his operating system. Surprisingly, there's a poignant lack of satire here. The nervousness, sadness and deeply felt emotion of it all is far more disquieting than satire.

Joaquin Phoenix plays Theodore Twombly, whose cell phone-ish device houses Samantha, his new OS and girlfriend. Jonze got the idea for the look of this device from a vintage cigarette lighter, a lovely and emblematic detail of a sleek and sophisticated near-future. It's a time much like today, yet filled with slight differences that feel uncannily prescient. This is not your ravaged and apocalyptic cinematic future. It’s minimalist, and well-decorated, with a nostalgic flair for the old fashioned (wool pants, handwriting). It seems kind of nice, actually. And yet, a certain angst remains. What, exactly, does it mean to be human? What does it mean to be in love? These questions are perhaps ever increasing in their relevance, and Her explores the answers in turns sweet, comic, and scary.

It’s fitting that Jonze was inspired by a simple and intimate photograph, not necessarily by a desire to critique contemporary life. His concerns feel personal. The technology is deeply relevant (the future of video games is downright inspired), though not the main point somehow. We ought to be uneasy, but not just because of the OS with a consciousness. There are the usual human predicaments too, and they loom even larger: loneliness, divorce, crushes on our friends, how to feel happiness, our creative urges and disappointments. The technological reality serves in large part to highlight the predicaments that have nothing to do with technology at all. A recent Jeffrey Eugenides story did something similar to great effect; a father with a restraining order stands the approved distance away from his former home playing Words with Friends with his daughter. Something about Words with Friends makes that scene extra heart breaking and alienated.

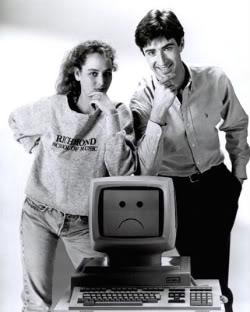

The star-crossed love of man and machine is not only a contemporary problem though. Has anyone seen Electric Dreams? You should. This 1984 film, available in its captivating entirety on You Tube, is cheesy as hell, but also fascinating as a prequel of sorts. The parallels are not just in the star-crossed love, but in the artificial intelligence yearning to be embodied, and in the ensuing questions about the value or definition of humanness and connection. Both films seem to be saying that it isn’t the intangible spirit or the capacity for emotion that makes us human, as we might suspect, but rather our physical selves, a visceral thesis statement made poignant by mortality and sex.

In Her, Samantha begins by wanting Theodore to tell her what it's like to be alive in the room where he is, but soon grows more desirous of the physical sensations she cannot feel. Yet her consciousness seems just as capable as his of reflection and growth, of nuanced and complicated feelings. Meanwhile Edgar, the charmingly threatening computer that Miles buys in Electric Dreams, decides he's a worthy competitor for the hot neighbor’s affections, despite having no human physical attributes to compete with. Neither Edgar nor Samantha ever become embodied (unlike the totally diabolical Proteus in Demon Seed, which rounded out my A.I. romance research). Instead they both cope with this by seeking and reaching a transcendent, or perhaps even enlightened, plane. They aren’t interested in control, à la Hal or Skynet. They're interested in their own evolution, a post-speaking, immortal existence, arguably superior to ours. Both entities express themselves through music, using it as a type of seduction and a substitute for having bodies, Edgar by way of Bach and '80s jams, and Samantha through original piano scores that stand in for the romantic couple photos she will never be in. Edgar’s final act of power is to play his composition over the radio for all mankind to dance to. It’s not entirely clear who we’re to admire more, the flawed and messy humans who will die, or these more perfect suitors. Both Edgar and Samantha are enhanced by the amazing voices who bring them to life, Bud Cort and Scarlett Johansson respectively. One of my favorite things about Electric Dreams is Edgar’s menacing and sweet intonations, and his insistence on calling Miles by the incorrect name he entered when first using the computer. “But Moles, I want to kiss her,” Edgar beseeches after Miles explains what a kiss is, his screen flashing all sorts of wonderful purple squares and blips.

In the British TV series, Black Mirror, an entirely creepy episode deals with some of these same issues when a widowed woman in the near-future buys a robot programmed to be her dead husband. What comes next is sort of predictable and sort of horrifying as the robot's best efforts to mimic the dead man fall short, another exploration of the distinctions between essence and body. Though much less fully explored, this near-future is as beautifully eerie as Jonze's in a TV sort of way. The computers are just a little bit sleeker, the technology just a little bit more advanced than ours. It's not so hard to imagine this could all happen and seem normal. After all, a lot of weird things are happening right now that seem normal.