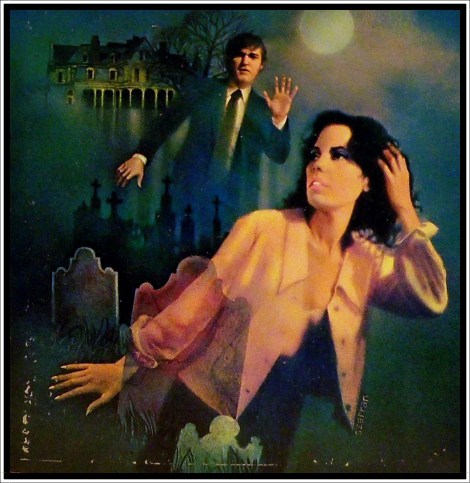

Google is making us stupid. Our phones are damaging our hearts. Zadie Smith thinks social media has us pathologically caught in the consciousness of a snarky teenage boy. Rebecca Solnit has some scathing observations about SF's tech boom. So too, I imagine our ephemeral Facebook connections must be leaving some psychological imprint on us, especially those friendships that we might not otherwise still have or want. On one hand I’m inclined to write off these concerns. The novelty of Facebook is gone for many of us; even my teenage students find it “boring” these days. So, does it really matter? In the early days of Facebook we all rushed to find everyone we could think of, amazed that it was possible, not considering whether we really wanted to or not. Part of the psychological imprint is that now we’re all somehow connected without actually interacting (sometimes without interacting in person and sometimes without interacting at all) to hundreds of people. Robert Kelly, my writing teacher in college, once told us that everyone we ever loved would exist forever as a ghost around us. I found that sad and thrilling and hoped it was true. He didn’t mean Facebook, but he certainly could have, and I'm less sure I hope it's true now.

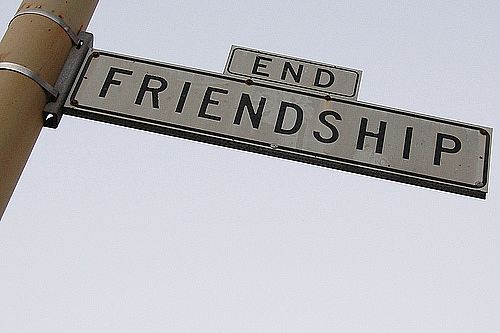

Recently I “unfriended” someone, an important person from my past who renders me an irrationally passionate teenager. And the unfriend is truly the last resort of the irrationally passionate teenager. In an era of sophisticated privacy settings I can hide anyone who annoys me and I can control every piece of information I share. The unfriend is unnecessary; it’s the violent, tangible act we turn to when no other expression of our over-it-ness will suffice. Where before door slamming and shouted threats of never speaking again would get the point across, it’s now the click that quietly disconnects us.

In the aftermath of this unfriend I conducted a casual survey and it seems many of my friends have never unfriended anyone. Reasons include fear of seeming too invested or concerned, of offending, of giving Facebook too much validity, that they might change their mind (though in what dramatic statement about an interpersonal dynamic might we ever be sure?) and so forth. They rightfully hide the offending party and continue on. It’s a reasonable and sustainable approach where no one’s feelings are hurt and we don’t seem crazy. After all, there are plenty of people I’ve merely hidden and soon forget. It’s easy, painless and non-political. I can unhide if I want and I don’t seem fickle. Due to this clandestine option, I forget half the people I’m friends with, but therein lies part of the strangeness and the question. Why do I stay invisibly connected to someone I want to hide, no matter what the reason?

I was curious as to why this particular person, and a handful before him, inspired me to forego such social niceties as would make sense. I wanted him to know he was no longer allowed to see me and that I had no interest in seeing him. Not only did I want to disconnect from him symbolically (and literally) in a way that he could potentially be aware of and upset by, but I was also willing to give up the idea that he might get the occasional glimpse at the curated, controlled moments of my perfect, amazing, digital life and I was thereby severing all ties, including the unspoken one where we’re at least allowed to spy on each other. All levels and layers of our connection are obsolete, says the unfriend. If the newsfeed hide is when you pretend you don’t see someone at a party, the unfriend is when you throw your drink in their face and cause a scene. Who actually inspires that? And even if they do, should we give them the pleasure?

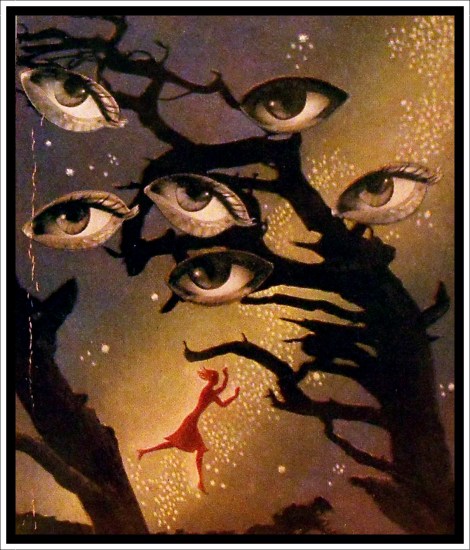

There have been others, albeit slightly less dramatic ones. The acquaintance who was a jerk the last time I saw him, who never sent a message or interacted with me, but silently sat there as my hundred and whatever-eth friend doing nothing. Finally, when I still couldn’t remember if I liked him in real life or not, I unfriended him. Or the guy who wanted me to “like” his band (ten times!) but walked by me in Dolores Park because he didn’t recognize me. Or the guy who took me on three dates in college and was a hell of a breakdancer but had nothing to say since. Or an old girlfriend who seemed to have forgotten clearly telling me we weren't friends anymore (in our early 20's). These people shouldn’t be connected to me because they aren’t. We don't know each other anymore or we never did. What does it do to my brain/heart/psychology to know they’re there anyway? We’re not even actively looking at each other's lives most likely, but instead just absent-mindedly, occasionally looking, listlessly and invisibly bound to one another. In what unconscious, tiny ways are we changed by revealing ourselves like this, by looking at others and being seen within this framework?