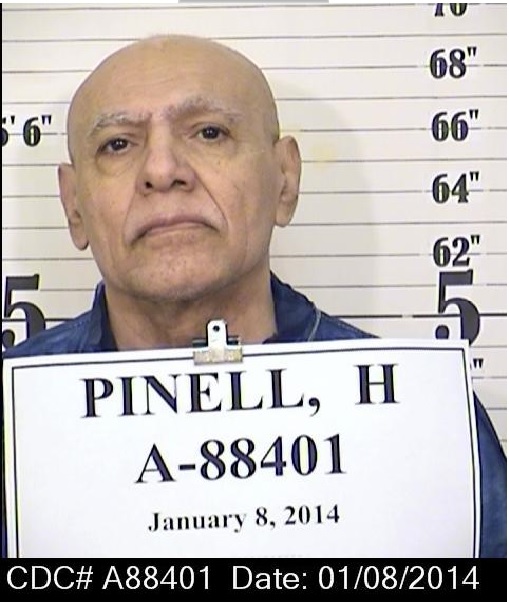

Pinell, nicknamed "Yogi Bear," was killed Wednesday by two other inmates in an exercise yard at California State Prison, Sacramento, prison officials said. His family may consider a wrongful death lawsuit, his attorney said Thursday.

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation spokeswoman Terry Thornton said that because the investigation is ongoing she could not respond to the criticism of his transfer to the general prison population on July 29, nor say if officials feared for Pinell's safety.

"They don't know why these two inmates attacked him yet," she said. "That's what we hope to learn from the investigation."

The slaying at the maximum security facility east of Sacramento triggered a melee by about 70 other inmates that sent 11 prisoners to outside hospitals with stab wounds, corrections officials said. Five remained hospitalized Thursday, one in critical condition.

Despite spending nearly all of his adult life locked up, Pinell maintained a strong following outside the prison walls.

He wrote long letters posted to a website by supporters, addressing the civil rights movement and the decades of solitary confinement that he likened to being "buried alive," with no contact visits with relatives or friends since December 1970. He was allowed a 15-minute contact meeting to marry a woman, who has since died.

Pinell survived repeated assassination attempts over the years even while he was kept isolated from other prisoners, first in administrative segregation cells and later in Pelican Bay State Prison's security housing unit with other purported gang leaders.

"He's had other prisoners throw bombs into his cell, shoot him with prison-manufactured guns, stab him and otherwise physically attack him," Wattley said. Most attacks were in the 1970s and 1980s, but Pinell had death threats as recently as this year, after he was moved to the prison dubbed "New Folsom" that houses about 2,300 inmates in the suburb 25 miles east of Sacramento.

Many of the assaults and threats were by members of the white supremacist Aryan Brotherhood, which wanted to kill Pinell for his purported involvement in the Black Guerrilla Family prison gang with San Quentin 6 ringleader George Jackson, who was killed in the escape attempt, Wattley said. Pinell long denied any gang connection, but decades ago he led other black inmates who refused to accept some prison policies.

"Being in this kind of confinement is terrible, yes, in many ways, but trying to make it in the streets is harder, more challenging, and we knew that, in the 60s, and that's why we were working hard to change and prepare for the streets reality," Pinell wrote in a letter posted on the website, which includes instructions on how to send him money and cards.

His supporters describe him as a political prisoner and "a revolutionary hero." In his letters, he described learning at San Quentin of the Black Liberation Movement and efforts to improve the lives of black prisoners.

"The story or the image about him and his leadership role morphed into an image of him as a leader of a prison gang, a violent prison gang," Wattley said. "At this point it's hard to discern what is fact and how much is fiction."

Pinell was initially sentenced to life in prison in 1965 for a San Francisco-area rape. He received a second life sentence for killing Correctional Officer R.J. McCarthy in 1971 at the Correctional Training Facility in Soledad, and a third life sentence for the San Quentin escape attempt after he was convicted of assaulting two correctional officers.

He was denied parole 10 times, most recently in May 2014.

Pinell's daughter, Allegra Taylor of Sacramento, would not comment when reached by telephone Thursday.

Pinell, who immigrated to the United States from Nicaragua as a child, is also survived by his mother, now in her 90s, and siblings, Wattley said.

Associated Press Correspondent Juliet Williams contributed to this story.

Original Post noon Thursday, Aug. 13:

An inmate involved in a bloody 1971 San Quentin escape attempt that left six dead has been killed by a fellow prisoner, corrections officials said Wednesday.

The slaying of Hugo Pinell, 71, triggered a riot Wednesday that grew to involve about 70 inmates at a maximum security prison east of Sacramento, said California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation spokeswoman Dana Simas.

"He was definitely the target," Simas said. She would not give more information about the alleged attacker for his own protection.

Once Pinell was attacked in a California State Prison, Sacramento exercise yard by his fellow inmate, "everyone else joined in," Simas said, including members of multiple prison gangs.

Eleven other inmates were taken to an outside hospital to be treated for stab wounds, while other injured inmates were treated at the prison. No employees were harmed. Guards fired three shots and used pepper spray to break up the brawl.

Officials initially said about 100 inmates were involved and five hospitalized.

Forty-four years ago, Pinell helped slit the throats of San Quentin prison guards during an escape attempt that led to the deaths of three guards, two inmate trustees and escape ringleader George Jackson, who was fatally shot as he ran toward an outside prison wall, according to Associated Press stories.

Jackson was a Black Panther leader, founder of the Black Guerrilla Family prison gang, and author of the 1970 book "Soledad Brother," written after he and other inmates were accused in the slaying of a Soledad prison guard in January 1970.

Guards testified that Jackson started the escape attempt when he pulled a smuggled 9-mm pistol from under his 6-inch-high Afro hairdo and fatally shot two correctional officers.

Correctional Officer Urbano Rubiaco Jr. survived to later testify that Pinell used a knife made of razor blades embedded in a toothbrush handle to slash Rubiaco's neck.

"He said 'I love you pigs' and then he cut my throat," Rubiaco said. He was one of two guards taken hostage by 25 inmates who were released from their cells during the escape attempt.

Correctional Sgt. Frank McCray testified that he and other guards were blindfolded, bound and piled into a cell, where McCray said his throat also was cut while other guards were shot and strangled.

A jury eventually acquitted Jackson's lawyer, Stephen Bingham, a grandson of former Connecticut Gov. Hiram Bingham, of smuggling in the gun.

Pinell and five other inmates became known as the San Quentin Six. Only one, 61-year-old William "Willie" Tate, remains in prison, at the Correctional Training Facility in Soledad.

The others were freed years ago: Fleeta Drumgo and Luis Talamantez in 1976, Johnny Larry Spain in 1991 and David Johnson in 1993.

Pinell was initially sent to prison in 1965 to serve a life sentence for a San Francisco rape. He was given a second life sentence for killing Correctional Officer R.J. McCarthy in 1971 at the Soledad prison.

He was given a third life sentence for the San Quentin escape attempt after he was convicted of assaulting two correctional officers.

Prisoners remained locked in their cells as officers investigated Wednesday's disturbance.