As Richmond prepared to enter the 1960s, the city was about to encounter an era of rapid change. In November of 1959, readers opened the pages of the city’s daily newspaper, the Richmond Independent, to be confronted with Thanksgiving sales and headlines about next fall’s presidential race (“State GOP Supports Nixon”).

The advertisements reflected an idyllic version of late 1950s America: A well-dressed businessman, hands clasped in his lap, dozes with a smile as a cherubic young boy gazes up in admiration from the next seat above the headline, “rest assured,” with Greyhound.

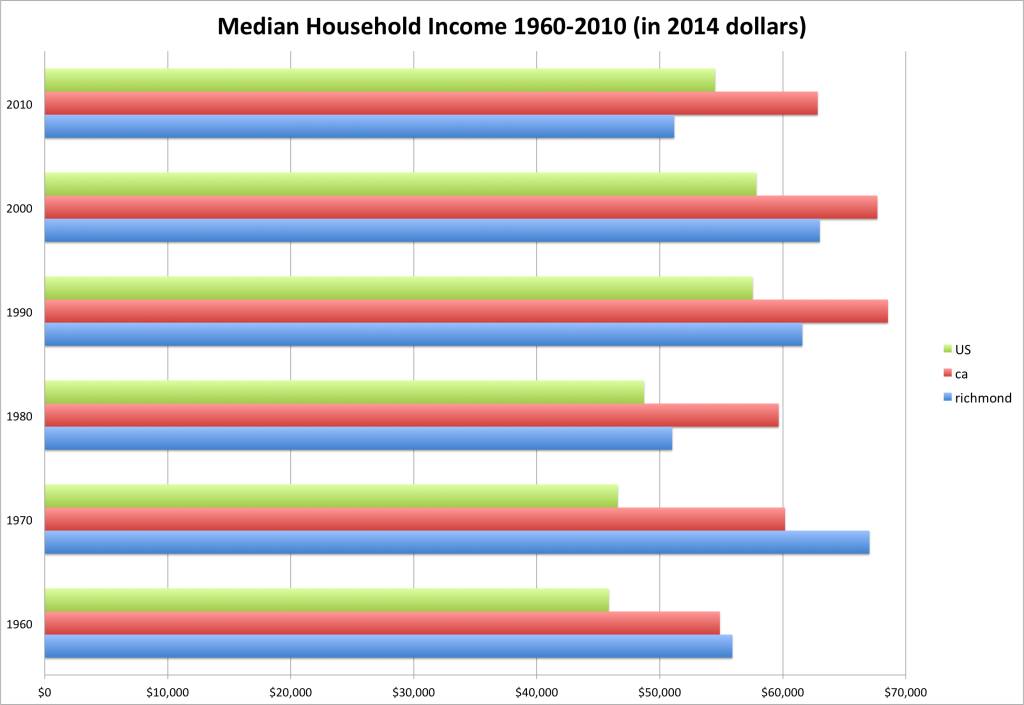

It was a time of expansion. The Richmond-San Rafael Bridge had been finished three years earlier, and the post-World War II shipbuilding boom was still driving Richmond’s economy. The city was solidly middle class. The city’s median household income exceeded both the state and national medians. New developments were popping up, spreading out into areas like El Sobrante, where new three-bedroom, two-bath houses were advertised in the newspaper for as little as $16,950, a little less than $140,000 in today’s dollars.

Most of the city’s commercial life took place in the central part of town, around Macdonald Avenue. Auto showrooms were commonplace. A new sedan at Plymouth Motors on Macdonald Avenue, where a 7-Eleven convenience store now stands next to Casper’s Famous Hot Dogs, cost $1,995, or about $16,400 today.

Several grocery stores dotted Richmond’s main thoroughfare, such as Nelson’s Shopping Center at 23rd and Macdonald Avenue, where Alta Coffee cost 47 cents a pound ($3.84 in today’s dollars) and three pounds of hamburger meat sold for a dollar ($8.22 today). A little further down the road, the downtown area boasted shopping at Macy’s and other boutiques, as well as movie theaters.