A Fiscal Lifeline

"Our schools, instead of laying off 30,000 people, we're now increasing the funding available by 30 percent for all the kids," said Brown in this season's only gubernatorial debate on Sept. 4.

The taxes collected under Prop. 30 have amounted to at least some $13 billion so far, according to the state controller's website tracking the funds. But the earmarking of those dollars for schools is only part of the story, as they helped provide a fiscal lifeline for the struggling state budget.

"More money from a tax increase like Prop. 30 means more money for other programs," says Jason Sisney, deputy analyst for the independent Legislative Analyst's Office.

That's largely because the 2012 initiative scored all of the new tax revenues as counting toward California's constitutional guarantee for K-14 school funding. Money that might have otherwise have gone to schools could then go to other budget priorities, from social services to debt repayment.

Prop. 30 increased personal income taxes on single filers making more than $250,000 a year and joint filers earning more than $500,000 a year. It also raised the state portion of the sales tax a quarter-cent from 2013 through 2016.

The total tax revenue collected by Prop. 30 continues to grow. Data from the state Department of Finance peg the projected revenue from the initiative this fiscal year at $7.4 billion, peaking at almost $7.7 billion in the fiscal year that begins next July.

But after that, Prop. 30's tax dollars start to fade ... which is where the uncertainty lies.

Brown's Gamble On California's Recovery

Think of the dimmer switch on a light. It doesn't turn the light off suddenly, it allows the light to be slowly faded down. Prop. 30 operates much the same way with the temporary taxes, turning them off slowly between 2016 and 2018. That fading impact affects four successive budget years for state government.

"The biggest variable," says LAO analyst Sisney, "is the economic environment that the state is in as the taxes phase out."

If California's economy grows, the sunset on the Prop. 30 taxes may be mildly felt -- or not felt at all. But if the economy sputters or stalls, the absence of some $7 billion in state general fund revenues could cause a big blow.

"The state's revenue situation could be pretty bad," says Sisney of that scenario.

For starters, the missing revenue could create more instability to school funding. The 2012 initiative did more than just temporarily raise some taxes; it also permanently transferred a portion of sales taxes to local governments to help finance Brown's 2011 realignment of public safety. Those sales tax revenues used to count toward setting the school funding levels ... but no longer.

In some scenarios laid out by budget analysts, the expiring Prop. 30 taxes could make schools financially worse off than they would have been if the transferred sales tax dollars were kept by the state. In other scenarios, the school funding guarantee would be higher because of Prop. 30. But that higher level of base funding might -- if the economy suffers -- put pressure on funding for other state services.

And all of this, say some of Prop. 30's most vocal backers, is why the governor should embrace something different from what voters were told in 2012.

Make Prop. 30 Taxes Permanent?

"I think there's absolutely no reason why we shouldn't make Prop. 30 permanent," says teachers union president Pechthalt.

The buzz over extending, or forever enshrining, the 2012 taxes began earlier this year and may hit a fever pitch when the new Legislature convenes in January. Key to the debate will be both the political muscle of tax supporters and the solid economic data, if any, about the impact of the taxes.

Two years ago, opponents of Proposition 30 warned that the temporary income and sales tax hike would impede California's economic recovery. Now the issue could simply be whether the current recovery would have been stronger.

Pechthalt argues that the past two years have shown growth and taxes are not incompatible.

"California has really set a model for the rest of the nation," he says.

Opponents, however, would likely focus on the part of the Prop. 30 story not really emphasized in 2012 -- the breathing room the tax revenues create for other expenses.

Anti-tax activist Joel Fox wrote earlier this week that extending the Prop. 30 taxes would simply make it easier to shore up underfunded public employee pensions:

When you see tax increases on the ballot think pension costs. Money in government budgets is fungible to some extent. If you cover specific agency costs with a tax increase, that frees up general fund money for other items, including pensions.

Whether the Legislature would consider extending the taxes, or making them permanent, is a function of the ballot box; Democrats may struggle next week to hold on to a supermajority of seats in each house, and losing that grip on power would all but kill any notion of action in the state Capitol (remember, tax increases require a two-thirds vote of both houses).

Even so, Brown has been adamant that voters should have the say on taxes. And he doesn't seem inclined to wage that campaign anytime soon.

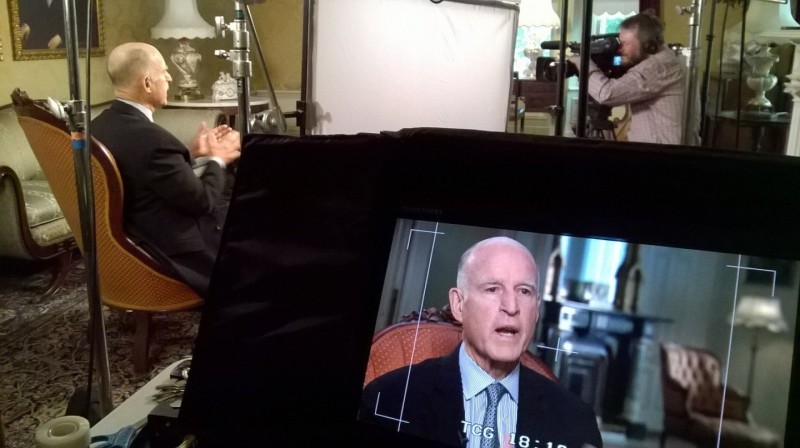

"I said when I campaigned for Prop. 30 that it was a temporary tax," the governor told KQED's Scott Detrow earlier this week. "So that's my belief. And I'm going to do everything I can to live within our means."