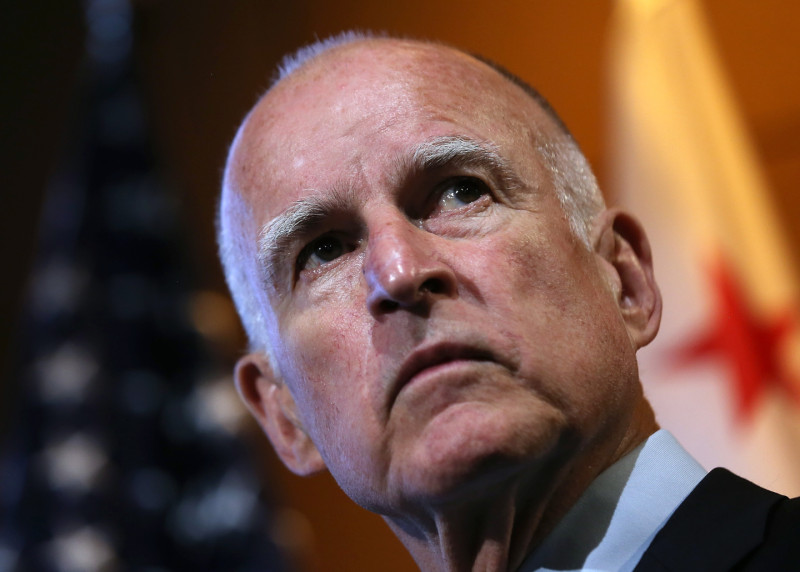

This week, Brown ever so slowly dipped his toes into the waters of the 2014 campaign season, sending two emails to supporters and then firing off a series of tweets in support of Proposition 1 and Proposition 2. Proposition 1 is the $7.5 billion water bond proposal facing voters; Proposition 2 is the new effort to create a more stable and viable cash reserve fund for the state budget.

(You can read about all the statewide issues in KQED’s new California Election Watch 2014 online guide.)

Brown played a key role in shaping both measures as they made their way through the state Legislature this year, and he has proclaimed both as essential to the Golden State's future.

"There are only two things," wrote Brown in one of the week's emails, "that could derail California's recovery: lack of water, and a return to the fiscal irresponsibility we've seen over the last few decades in Sacramento."

But are ballot measures really the way to take a measure of the man? Yes, says his political team.

"The props," said Brown adviser Dan Newman, "are inextricably linked with his philosophy, his agenda, his priorities."

In truth, Brown was skittish for much of the legislative year about a multibillion dollar water bond on the fall ballot. After all, when you're boasting about your efforts to reduce the state's debt, it can be a bit awkward to then ask the voters to add to that debt. In the end, though, the politics of the drought probably convinced him to strike the deal that became Prop. 1.

Prop. 2, on the other hand, has always been pitch-perfect for Brown. The proposition's "tough-to-raid-the-piggy bank" plan for a new state savings account, coupled with insistence on paying off debt, are very much in line with the governor's message these past few years.

Taken together, they no doubt present an electoral narrative much to Brown's liking.

The propositions "give him substantive issues to talk about," said GOP strategist Stutzman. "They put him in campaign mode, but in a policy context."

They do not, however, give the actual race for governor much oxygen. And that has left Neel Kashkari, Brown's long-shot, newcomer challenger, doing a lot of shadow boxing. The Republican has kept a busy campaign schedule, speaking to small groups around California and even joining in barnstorming treks with other GOP statewide contenders.

But his now-familiar jabs at Brown -- that the governor can't relate to average voters, that he's failed to focus on things that could spark the economy in still-distressed parts of California -- have hardly left a mark on the governor. In fact, Team Kashkari isn't even taking the bait to criticize Brown for ducking the campaign; they declined to comment when contacted for this story.

Early polls show that the Prop. 1 water bond is in good shape, while Prop. 2 is struggling -- perhaps because voters don't yet understand it. That certainly sounds like the kind of professorial task that Brown enjoys. Kashkari took a small swipe at the water bond in the candidates' only debate on Sept. 4, but it's doubtful he's going to spend much energy criticizing either measure.

While Brown's popularity is wide, it's hard to call it deep. After all, recent statewide surveys show a lot of voters still think California is on the wrong track, and they don't overwhelmingly approve of how Brown has done his job. Still, they also don't seem to have found a reason to cast their lot with the new guy, who not only has raised less than half the money that the incumbent has since Labor Day ($995,000 to $394,000), but is staring at that incumbent's already existing $22.3 million war chest. He is also behind in the most recent public poll by 21 points.

Even four years ago, in a closely watched and expensive slugfest of a race, Brown resisted calls to fully launch his campaign before the last lap. In 2014, with those dynamics long gone, it's hard to see the incumbent governor really making the case for a final four years until he can almost touch the yellow tape stretched across the finish line.