http://www.kqed.org/.stream/anon/radio/tcrmag/2014/05/2014-05-16e-tcrmag.mp3

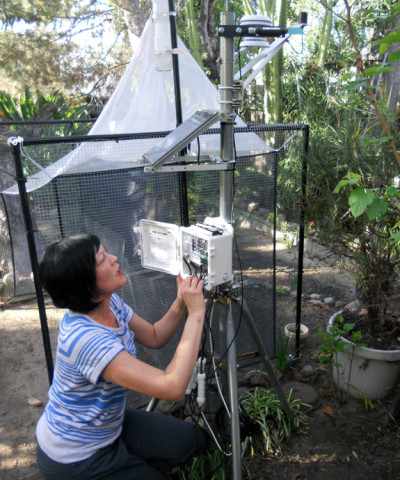

On a sloping hillside yard in the Highland Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, entomologist Lisa Gonzalez kneels to get to work. She's securing the stakes of a 5-foot-tall insect-catching trap made of netting. Homeowner Natalie Brejcha and her daughter, Tenny, look on.

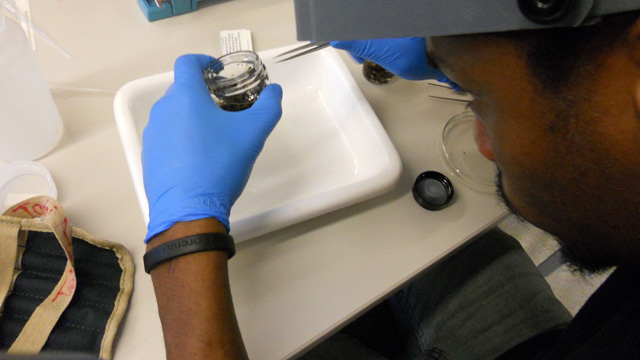

"Insects are basically just randomly flying by," explains Gonzalez. "It's open on two sides. The insects get intercepted by this trap. If you notice, it's darker on the bottom and lighter on the top. Well, if insects are trying to escape, they're going to go towards the light, and toward the apex of the trap. There's a little hole at the top of the bottle, so they fall in and they get collected in the ethanol."

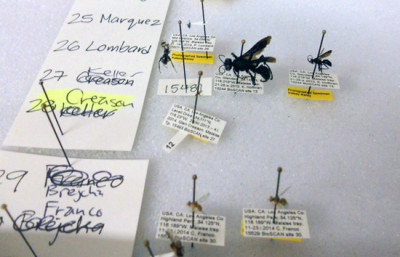

The setup is part of a groundbreaking study being conducted by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. It will be one of the most sustained looks at insects in an urban environment ever, and it's happening with the help of 30 property owners across the city. For the next three years, they'll all host traps like these in different parts of the city. The idea, in a nutshell, is to understand the effects of urbanization on living creatures.

"What we're really interested in doing is understand the effect of urbanization on organismal biodiversity," says study manager Dean Pentcheff. "So how is it that we, as we civilized this city — paved it over, diked it, dammed it and channelized it — how have we affected the biodiversity here? The tool we're using to study that is insects. So if you want to study biodiversity, you pick the most biodiverse species on the planet."

Indeed, the stats on insects are impressive: Scientists know of roughly 1 million insect species now, but they estimate there are probably closer to 10 million on earth. Every week, each site participating in the study is collecting hundreds of bugs. Most participants found out about the study through the Natural History Museum, and they do have some responsibilities. They're all expected to change the jars once a week and keep an eye on the trap. But to Natalie Brejcha, it’s no problem.