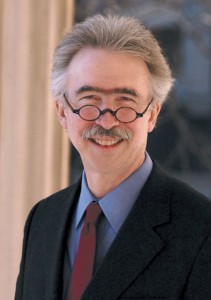

Here's the announcement from the university. It's Nicholas B. Dirks, Columbia University’s executive vice president and dean of the faculty of Arts and Sciences, who not only appears to be very accomplished as an academic, but looks like he plays one on TV.

He'll replace Chancellor Robert Birgeneaum, who's stepping down at the end of the year.

The university says the UC Board of Regents will vote on the appointment in late November. The LA times reports Dirks' proposed salary, which the Board has to approve, "was not publicly released pending negotiations. Birgeneau’s salary was $436,800 a year and Dirks is expected to be paid at least that."

Here's Dirks' web page at Columbia. According to his bio, Dirks received an undergrad degree in Asian and African Studies at Wesleyan and a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago's Dept. of History. He's taught at the California Institute of Technology, the University of Michigan, the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, and the London School of Economics.

More...

His major works include The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom (Cambridge University Press, 1987); Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India (Princeton University Press, 2001); and The Scandal of Empire: India and the Creation of Imperial Britain (Harvard University Press, 2006). He has edited several books, including Colonialism and Culture, (University of Michigan Press, 1992), Culture/Power/History: A Reader in Contemporary Social Theory (Princeton University Press, 1994), and In Near Ruins: Cultural Theory at the end of the Century (University of Minnesota Press, 1999), and published more than forty articles on subjects ranging from the history and anthropology of South Asia to social and cultural theory, the history of imperialism, historiography, cultural studies, and globalization. He has done extensive archival and field research in India as well as in Britain. He is currently working on a book concerning the last years of British rule in India and the growing role of the United States in South Asia, as also a book entitled, The University and the World: The Opening of the American Mind.