Leafing through the 84 pages of decision and dissents from the U.S. Supreme Court today, the first sign you're in unusual territory is the pictures. The majority opinion from Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy includes three images depicting conditions in California's prisons. Two show generic scenes of overcrowding in a system that in 2006 was packed to 185 percent of its designed capacity. (One unforgettable portrait of the overflow conditions came from NPR's Laura Sullivan in a 2008 story on San Quentin.)

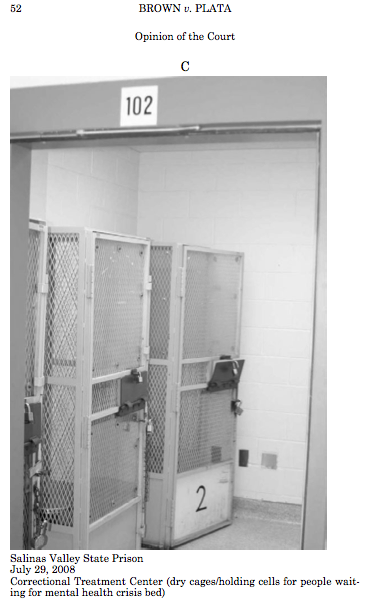

A third image (right) shows cages used to confine some mentally disturbed prisoners. Here's how the opinion describes them: "Because of a shortage of treatment beds, suicidal inmates may be held for prolonged periods in telephone-booth sized cages without toilets. ... A psychiatric expert reported observing an inmate who had been held in such a cage for nearly 24 hours, standing in a pool of his own urine, unresponsive and nearly catatonic. Prison officials explained they had 'no place to put him.' "

(By the way: the use of images in U.S. Supreme Court opinions: rare but not unprecedented. For instance, see the 2003 opinion Van Orden v. Perry, in which the court held that a display of the Ten Commandments on the Texas state capitol grounds did not violate the First Amendment's establishment clause.)

The court was divided 5-4 in today's Brown v. Plata. But even that close result masks the bitterness of the split. The 84 pages comprise Kennedy's majority opinion—joined by Associate Justices Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan—and two dissents: one by Antonin Scalia (joined by Clarence Thomas) and one by Samuel Alito ( joined by Chief Justice John Roberts.) The dissents are incendiary, but more on that in a moment.

The majority opinion may be read as a condemnation of inhumane conditions in California prisons and as a ringing defense of the notion that under our Constitution society owes those we imprison a basic measure of rights:

"As a consequence of their own actions, prisoners may be deprived of rights that are fundamental to liberty. Yet the law and the Constitution demand recognition of certain other rights. Prisoners retain the essence of human dignity inherent in all persons. Respect for that dignity animates the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. ' "The basic concept underlying the Eighth Amendment is nothing less than the dignity of man." ' (Atkins v. Virginia 2002, Trop v. Dulles 1958.)

"To incarcerate, society takes from prisoners the means to provide for their own needs. Prisoners are dependent on the State for food, clothing, and necessary medical care. A prison’s failure to provide sustenance for inmates 'may actually produce physical "torture or a lingering death." ' (in Estelle v. Gamble 1976, in re Kemmler 1890). ... Just as a prisoner may starve if not fed, he or she may suffer or die if not provided adequate medical care. A prison that deprives prisoners of basic sustenance, including adequate medical care, is incompatible with the concept of human dignity and has no place in civilized society."

But today's decision actually turns on something a little more mundane than the principles underlying the Eighth Amendment. The court's charge was to adjudicate the California's challenge to lower federal courts' findings and prescriptions for the prison system under a 1996 law called the Prison Litigation Reform Act, or PLRA. The law seeks to make it harder for prisoners to sue over the conditions of their incarceration and requires both inmates and the courts that hear their cases to jump through a series of hoops in seeking and granting remedies to situations like dangerously inadequate mental health care—the allegation that drove the original federal court case (now known as Coleman v. Brown et al.). For instance, inmates must show they've exhausted every available avenue for resolving a complaint inside prison—using the prison's grievance procedures, say—before suing. The law also requires a special three-judge panel, rather than a single judge, to pass judgment on relief for prisoner lawsuits. In granting relief, a three-judge panel is required to come up with a sharply focused remedy to fix a constitutional violation. The panel must also give "substantial weight" to how its remedy will affect public safety.