Was Rose Pak a power broker? Demonstrably yes.

Was she also a kingmaker? Arguably so.

And in Pak’s last days before her death, was she a “lion in winter,” as San Francisco Magazine dubbed her, leading a pride of politicos she had long mentored through a final campaign struggle? Perhaps inspiringly, yes.

But the film about her life, Rally, which premiered Friday at the 2023 San Francisco International Film Festival, manages to show the thread that binds all of those efforts, and the motivation behind the decades Pak spent shaping San Francisco political life.

“At the end of the day, everything she did, every person she talked to, it was about enhancing the community and making the community better, and she was very vocal about that,” San Francisco Police Department Commander Paul Yep told me, standing among Pak’s friends at an after-party celebrating the film.

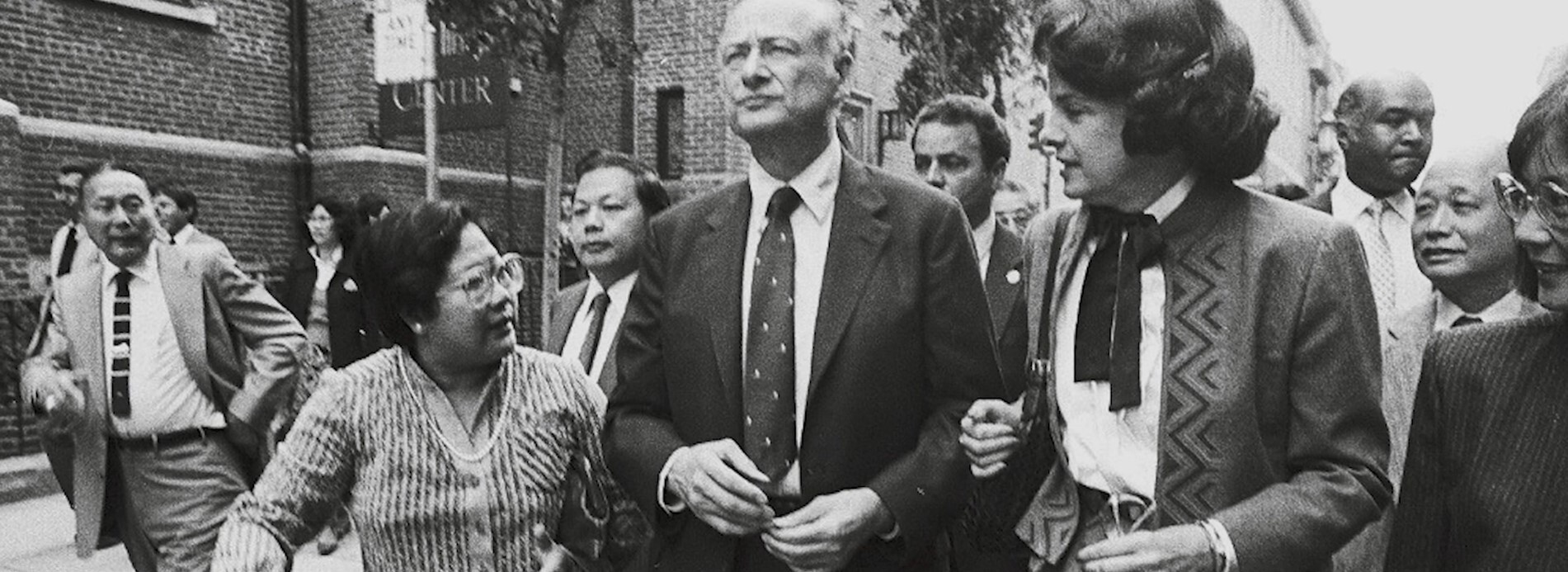

Pak, who was born in China, came to San Francisco in the 1960s to work for the San Francisco Chronicle. She would eventually become one of the city’s most influential political figures, channeling the Chinese community to lift people into power, who would in turn fulfill promises to Pak to help Chinese San Franciscans.

Yep remembers Pak’s care for Chinatown well. At their first meeting, Pak told him, “If you’re about the community, then I’m there for you.”

That’s a lesson that’s obvious to her friends, many of whom were in attendance for Rally’s premiere at the CGV San Francisco 14 cinema on 1000 Van Ness Avenue on Friday night. Yet somehow it was a message lost on many San Franciscans over the years.

In the film, news clips spanning decades repeatedly describe Pak as a “powerful influencer” behind the scenes, a “shadowy figure” pulling the puppet strings of San Francisco’s power structure. She would often describe the term “power broker” as racist, musing, If she were white, wouldn’t they say “civic leader”?