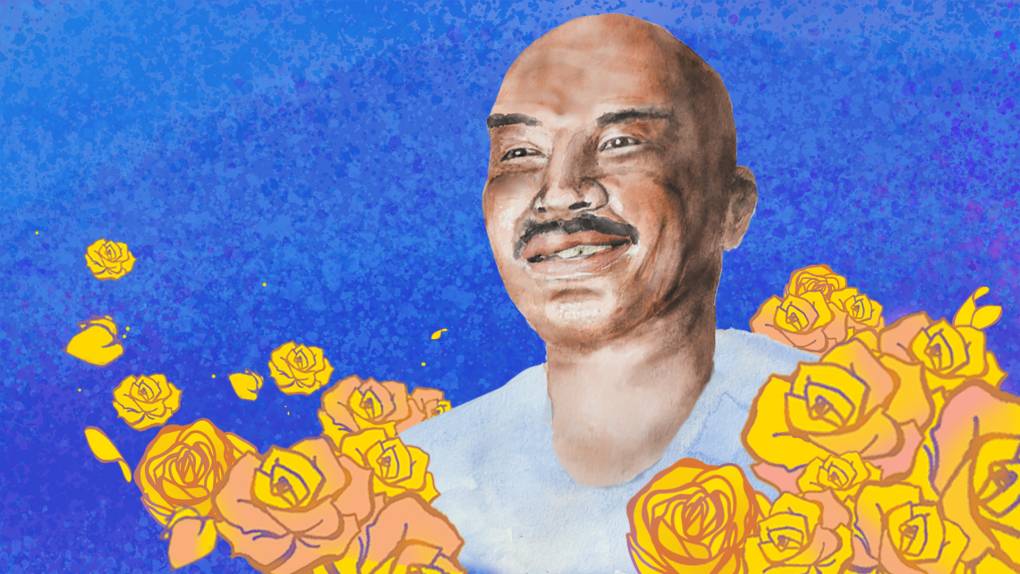

More than 60,000 Californians have died from COVID-19. This week, The California Report Magazine is launching a series to remember some of them. Our first tribute is to Eric Warner, who died of COVID-19 in San Quentin State Prison at age 57. He was born and raised in San Francisco, the son of Filipino immigrants. He was a barber, a boxer and a beloved brother. Eric’s older brother Hank brings us this tribute.

H

aving an only brother incarcerated for life leaves a hole in your heart. You long for sibling companionship. And guard your secret for fear of shame.

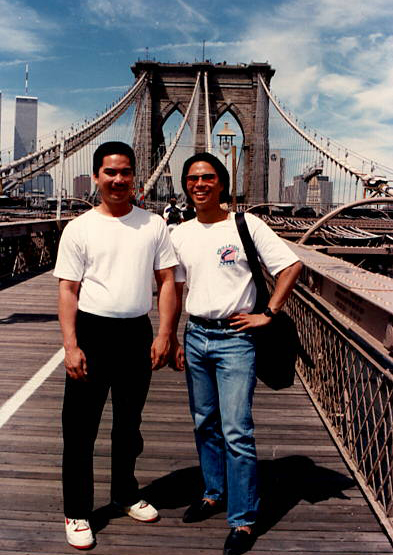

Growing up, we collected pollywogs after big rains. We adventured new horizons on bikes, imitated major leaguers in the schoolyard. Life was simple. We happily sang along to Don McLean’s "American Pie," oblivious to the foreshadowing of things to come.

By our teenage years, Eric and I drifted in opposite directions. As adults, I only saw him at times of crisis, like when he lost his leg in a tragic car accident, or when I visited him at county jails and hard-to-reach penitentiaries.

As he began serving his life sentence, we reconnected through hand-written letters.

I committed to helping Eric survive. He needed a life of meaning and purpose. For more than 20 years, we talked about spiritual guidance and emotional fulfillment. Like workout partners, we had a regimen for building his mental and emotional strength.

Complete transformation came after he graduated from rehabilitation programs. San Quentin’s intense workshops gave Eric the tools to conquer his demons. He learned how to live a life of redemption.

“E” – as he was known in the pen – studied law in the prison library. He handled his own appeal and successfully reduced his life sentence. But California’s three strikes law, the root problem to over-sentencing and deadly overpopulation in prisons, prevented him from ever seeing freedom.

His resolve would not be broken. E used his valuable new skills to help hundreds of incarcerated men fight for their legal rights. He became known as the “Prison Lawyer.”

"Now, think about advocacy from prison," said Adnan Khan in a tribute video to Eric on Facebook. Khan was formerly incarcerated himself and now runs a national organization called Re:Store Justice.

"From a level-four prison. Doesn't have a law degree. A dude serving a life sentence, but passionate about helping people," Khan said. "He helped others. Never charged no one, and said, 'Just don't forget me when you get out.' That's who Eric was, and is."

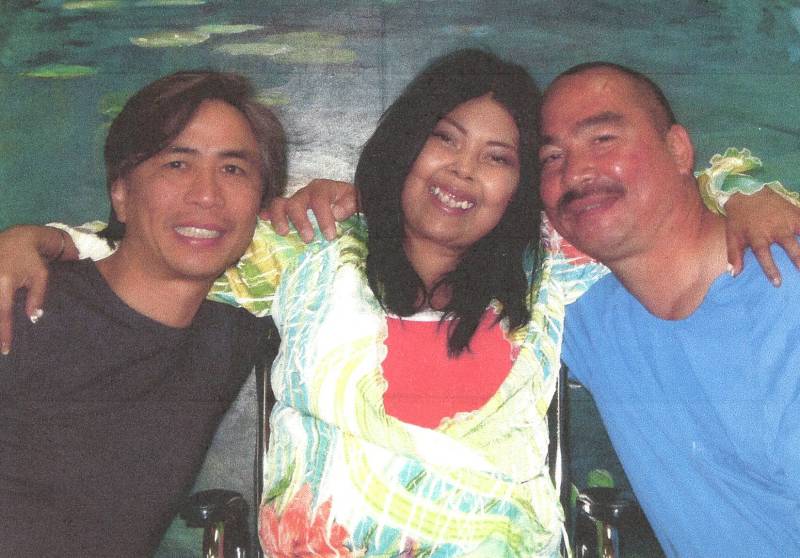

In addition to me, Eric had Amanda, his fiancee.

They met when a close friend introduced his sister-in-law to Eric over the phone. Love letters and phone calls quickly ensued. They inspired one another to live with dignity. Amanda had late-stage cancer.

It was the only time they met in person. It was magical. I had never seen my brother this happy. That was back in 2019.

Eric talked about their love story, and read a letter to Amanda, in this documentary called “Resilience” — made by Khan and other incarcerated men learning to be filmmakers inside San Quentin:

Last summer, when I saw on the news that there was a COVID outbreak in San Quentin, my heart sank. I didn’t hear from Eric for weeks. We normally talked on the phone every Sunday. But there were no phone calls, no letters, no news.

On July 18, 2020, I received a call from a nurse. Eric was hospitalized. He made it out of prison, only to end up in a hospital close to where we grew up. He had been in the ICU for over a week.

Facetime was the only way we could visit. Eric’s face, dominated by an air mask, filled my iPad screen. The whooshing sound of the breathing machine drowned out his voice. He gasped for life with every breath. Our visits lasted only a few minutes. I was his cheerleader and soother.

It was just the two of us for seven days, and then he passed.

Soon after Eric died, I received an overwhelming number of texts and phone messages. Formerly incarcerated men and prison staffers reached out to express their condolences.

All had to let me know how much Eric meant to them.