It's clear library patrons want to borrow e-books, and libraries want to lend them, but because e-book formats, e-readers, and agreements with publishers evolve rapidly, no one has figured out how to make it all work smoothly.

OLD SYSTEMS FOR NEW TECHNOLOGIES

In some ways, publishers artificially impose limits on e-book lending to create the same scarcity and demand that exists with printed books. According to the report, "In general, publishers' e-book lending restrictions often attempt to mirror the logistics of print lending -- for instance, only allowing an e-book to be lent out to one patron at a time through a 'one book, one user' arrangement."

At the same time, cuts in library budgets in recent years and publishers' restrictions on purchasing have made it impossible for libraries to acquire enough e-books to keep up with the demand. A report released last week by the American Library Association, "Libraries Connect Communities: Public Library Funding & Technology Access Study 2011-2012," found 56.7 percent of American libraries had reduced or flat operating budgets over the past year.

One librarian wrote in the Pew survey, "We boycott HarperCollins due to their use limitations. (Books must be repurchased after 26 checkouts.) We can only purchase one copy per title from Penguin (resulting in extremely long hold lists and disgruntled patrons). Random House has upped their prices to around $100 per copy, so we are only purchasing the top 10 bestsellers from this publisher. I fear what will happen in the next year."

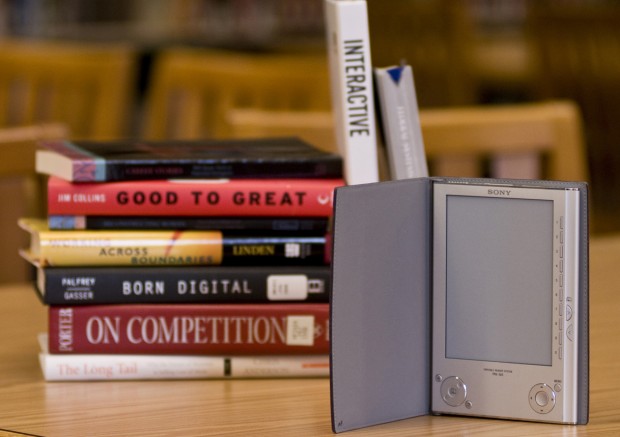

Some libraries simply can't keep up with the rapid changes in technology due to time and budget limits on their staff. Some librarians might know their way around a Kindle or a Nook, but not an iPad. While better-funded library districts report offering e-reader training sessions and vouchers for librarians to purchase their own e-readers, many of the librarians who responded to the survey indicate their staff is more likely to be self-taught through their own use of personal tablets and e-readers than they are to receive formal training.

This mirrors how the general population is learning about e-reading. According to the report, "Many mentioned having a spouse, child, or friend who is more tech-savvy than them and serves as an inspiration or teacher."

Several librarians indicated that there is one particular staffer who understands technology better than others and fulfills that go-ask-your-little-brother role, with less tech-comfortable librarians sending people to the resident tech guru with their questions.

Libraries' acquisition of printed books was gradual, but many patrons expect the acquisition of e-books to be instant. Some of the surveyed e-book readers imagine a future library where every book ever published is available to patrons instantly, for free, with no wait lists or limits on checkout time.

But the ghosts of technologies past provide a warning for libraries that might rush to invest too many resources in one digital format. According to the report, some librarians "mentioned cutting increasingly obsolete resources, like collections of cassettes or VHS tapes, as well as databases that are rarely used." Meanwhile, old-fashioned print books continue to circulate.

PUBLISHERS' REVENUE

While librarians disagree with the publishers' e-book policies, they seem to be working for the moment. A report from the Association of American Publishers released earlier this month showed that for the first time, American publishers are earning more revenue from e-books than hardback books. In the first quarter of 2012, e-books brought in $282.3 million, while hardbacks earned publishers $229.6 million. The revenues from paperback books still have a slight edge over those categories, but paperbacks are slipping, with earnings from adult trade paperbacks falling by 10.5 percent and adult mass-market paperbacks tumbling by 20.8 percent since last year. For publishers and writers, so far it seems the advent of e-books takes away as much as it gives.

The restrictions publishers place on library e-book lending are helping them maintain the delicate balance between what e-books are earning and what they are costing. Many of the people surveyed by the Pew Center indicate they find it much more convenient to simply purchase an e-book outright than to wait for it to become available at the library.

NOT YOUR MOTHER'S LIBRARIAN

The role of the librarian as someone eager to help patrons with their questions about the capitol of Peru or the state bird of Colorado has faded in recent years. One librarian told Pew, "Instead of print indexes or even online databases, many people just Google everything and if they find something 'good enough,' they don't come to or contact the library for help."

Many library users indicate that most of their interaction with libraries these days is via the computer, through which they either download e-books, sign up on wait lists, or request printed books which they then pick up on the hold shelf rather than visiting the library and lingering in the stacks.

But that doesn't mean librarians have a lot of free time -- on the contrary, they have become even busier answering patrons' questions about technology. One librarian wrote, "It takes a long time to explain and walk patrons through the downloading process -- about half an hour from start to finish most times -- and we often feel rushed at the public assistance desk because there are often other demands on our time."

Pew's "Libraries, Patrons, and E-books" report makes it clear that Americans are more interested in e-books and eager to borrow them from libraries than ever before, but the expansion of the information superhighway has happened so rapidly for everyone involved -- libraries, publishers and readers -- that it is riddled with potholes.

Apparently, it will take a nation of little brothers to bring us all up to e-reading speed.

Jenny Shank is the author of the novel "The Ringer" (The Permanent Press, 2011), a finalist for the High Plains Book Award.

By Jenny Shank

By Jenny Shank