In the midst of this multimedia blitzkrieg, the importance of mindfulness and focused attention is rising. If we can't cultivate mindfulness and focused attention while sitting quietly in a room, then how can we expect to bring these qualities of mind into turbulent circumstances -- both on and offline?

FRACTURED ATTENTION, FRACTURED MIND

The average American consumes 34 gigabytes of content and 100,000 words every single day, according to the 2008 report from UC San Diego. To put these numbers in perspective, one gigabyte is a symphony in high-fidelity sound or a broadcast quality movie.

Our colossal consuming habits are not only crowding out essential neurological downtime, but they're creating a chemical addiction that has interest in little else. When we consume media -- from watching TV to surfing the Net, and from playing videogames to using social media -- we're triggering the brain chemical dopamine. Dopamine creates a "high," and we are wired to do what it takes to maintain this elevated state. When the dopamine levels decrease, we begin to look for diversions that will restore the high.

In the absence of stimulation, and the corresponding dopamine high, we're likely to feel bored. As a result, many of us become stimulation junkies and incessant multitaskers. In the New York Times article, "Attached to Technology and Paying the Price," Matt Richtel wrote, "While many people say multitasking makes them more productive, research shows otherwise. Heavy multitaskers actually have more trouble focusing and shutting out irrelevant information, scientists say, and they experience more stress ... And scientists are discovering that even after the multitasking ends, fractured thinking and lack of focus persist. In other words, this is also your brain off computers."

THE ANTIDOTE: MINDFULNESS

Living in a connected age is double-edged. While policy and regulation have their place within this matrix, it seems that human agency should be the keystone. Therefore, for the body politic to walk the edge between being empowered by our connectivity or hindered by it requires a steady dose of mind training.

Research at Duke University underscores why. Researchers found that more than 40 percent of our actions are based on habits, not conscious decisions. Unconscious habits and assumptions aren't destiny, but if we don't bring them into focus then the force of these habits will continue to chart our course.

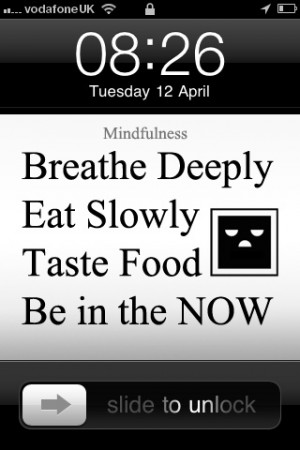

The practice of mindfulness is a time-tested antidote to operating in autopilot.

"Mindfulness practice," according to Jon Kabat-Zinn, a pioneer of mindfulness-based stress reduction, "means that we commit fully in each moment to be present; inviting ourselves to interface with this moment in full awareness, with the intention to embody as best we can an orientation of calmness, mindfulness, and equanimity right here and right now."

While the technique of mindfulness isn't hard, developing a disciplined practice can feel like an Olympic challenge -- which is where education comes in.

MIND TRAINING IN SCHOOLS

Flickr: Neeta Lind

The direction in which education orients a person, to paraphrase Plato, will determine their future in life. While educational aims should be varied, an underlying goal should be in focusing student awareness in a metacognitive direction. If schools hope to prepare students for our hyper-connected world, it reasons that training students to be proficient with digital tools is only part of the equation.

Students must also be mindful of how digital tools and perpetual web connectivity are shaping their brains, perceptions and habits.

To that end, several promising studies have demonstrated the power of mindfulness mediation in schools to improve executive functioning, reducing stress, anxiety and aggression.

In his book, Techgnosis, Erik Davis also sees another value in integrating mind training into schools: