Interestingly, this process – known as indeterminate sentencing – became increasingly unpopular among both conservative and liberal politicians: conservatives expressed concern that parole boards were releasing inmates too early, while liberals alleged that the boards too often made discriminatory decisions based on factors like race.

Interestingly, this process – known as indeterminate sentencing – became increasingly unpopular among both conservative and liberal politicians: conservatives expressed concern that parole boards were releasing inmates too early, while liberals alleged that the boards too often made discriminatory decisions based on factors like race.

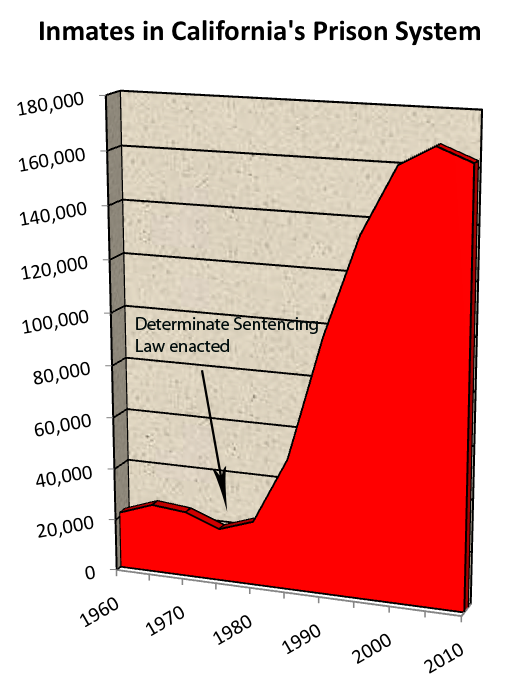

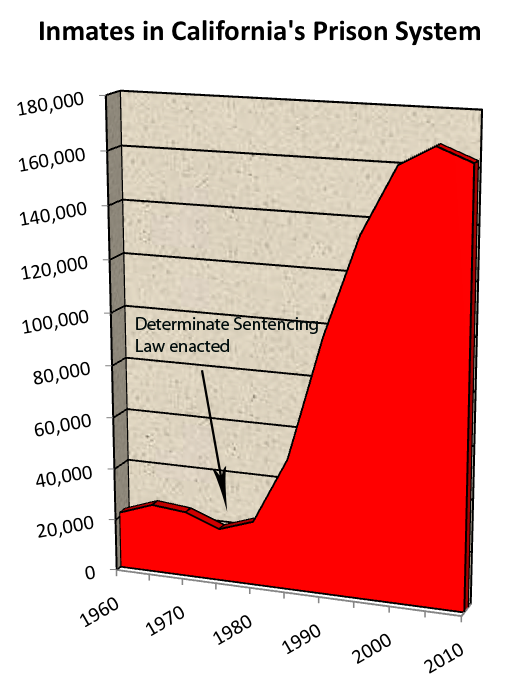

Determinate sentencing

Determinate sentencing was intended to make that process less arbitrary. After1977, the vast majority of convicted felons received fixed -- or "determinate" -- prison terms, and no longer appeared before a parole board prior to release. The legislature decided on "triads" of specific sentence lengths for certain crimes. So, whereas previously, a specific crime might have gotten you one to 20 years, the exact same crime was now punishable by a strictly defined term of, say, two, four, or six years.

Trial judges were required to impose the middle sentence unless overriding evidence justified a lower or higher term. In 2007, however the U.S. Supreme Court in Cunningham v. California invalidated this last part of the law, ruling it in violation of the Sixth Amendment's trial by jury requirement.

California's new sentencing system effectively diminished many of the incentives inmates had to seek rehabilitative services. Prison terms were now pretty much set in stone regardless of good or bad behavior (with the exception of a very modest fixed reduction for basic good conduct). And as a result, increasingly fewer resources were directed towards rehabilitative services.

The big increase

As violent crime rates around the country rose in the 1970s and 1980s, so too did tough on-crime political positions, especially in California. Determinate sentencing gave state lawmakers the authority to decide on and change the length of prison sentences. And because few elected officials wanted the liability of appearing soft on crime, the legislature kept jacking up prison terms for a variety relatively minor offenses.

In the two decades after the enactment of determinate sentencing, state legislators enacted nearly 100 laws that significantly enhanced sentences for various felonies. In particular, harsher punishments for non-serious, non-violent crimes like drug offenses resulted in the long-term incarceration of thousands of offenders who, previous to 1977, may have received only very brief terms or not gone to prison at all.

When interviewed in 2007, three decades after signing the determinate sentencing law, Jerry Brown expressed regret. He noted that “determinate sentencing, as it has worked out, is itself arbitrary."

During that thirty year period, the state’s prison population increased by nearly 900 percent.

The Parole Factor

The nature of parole changed as well after determinate sentencing took effect. Parole used to basically mean early release. Determinate sentencing pretty much eliminated that possibility. Since 1977, almost all released offenders (non-lifers) get placed under parole supervision for up to three years, during which time the ex-offender is "supervised" by a parole agent and required to follow specific conditions.

In theory, the system is intended as much to make sure ex-offenders stay out of trouble as it is to help with their transition back into society. But In actuality, the parole system is sorely lacking in the extent of the very needed resources it's able to provide. And many parolees get sent back to prison as a result of minor technical violations (called "administrative returns"). In short, parolees receive few services and walk on very thin ice. They can be sent back to prison for slip-ups as mundane as not showing up for parole visits or failing drug tests.

California's recidivism rate in 1977 was about 15 percent. Today, close to 70 percent of all ex-offenders return to prison within just three years, among the highest rates in the country.