Rooftop solar can make a sizable dent in the West’s renewable energy needs

This week representatives from the federal Department of Energy and Bureau of Land Management wrap up their California barnstorming swing, to gauge public opinion on the topic of siting solar projects. Throughout this often contentious debate, many have claimed that a potentially huge piece of the power solution is being overlooked; rooftop solar.

Fly into Ontario airport in Southern California’s Inland Empire — or just zoom in on Google Earth — and you’ll see hundreds of block-long warehouses. There are acres — probably square miles — of flat, gray roofs sizzling in the San Bernardino County sun. Soon, though, instead of merely soaking up the rays, hundreds of industrial rooftops in Southland cities will harness them to feed the local electrical grid.

Southern California Edison and independent power producers holding contracts with the utility are building 500 MW of solar panels on warehouses and, to a lesser extent, on the ground at other Southern California locations.

Together these projects are expected to produce enough energy to rival a traditional power plant, enough to serve about 325,000 homes.

Last fall, as the project was being ramped up, Edison’s rooftop solar manager Rudy Perez guided me through waves of deep blue panels—11,000 in all — atop an Ontario warehouse. “They’re the same standard type of panel you’d get on a residential photovoltaic system,” he said, adding that the company will also deploy more efficient SunPower brand panels.

I was intrigued by the project because, for years, environmentalists have advocated this kind of energy, called “distributed generation,” as an alternative to the environmental concerns that often attend other power sources, including out-of-town solar farms. The typical response from utilities has been, It’s just too expensive.

But the cost of solar panels has come down, and the sheer size of Edison’s project has allowed it to secure deep discounts, both on equipment and the installation costs. Plus, as the state’s solar industry has matured, there are more contractors with the experience to take on this kind of project. Perez estimates the installed cost for its portion of the project will be $3.50 a watt (conventional photovoltaic installations were running around $7 a watt when the project was launched).

That’s still more expensive than other power sources, including a large solar farm (plus transmission lines) in the Mojave desert.

But distributed solar has other advantages. It can feed directly into neighborhood electrical circuits, alleviating the need for new transmission lines. And, with virtually no public opposition, no requirement for environmental review (just local building permits), distributed solar is basically a sure bet and relatively speedy. Although the entire project will take five years to complete, a single site can be up and running in nine months.

The company’s VP of Renewable and Alternative power, Marc Ulrich says the project will help diversify Edison’s renewable power portfolio: “You need multiple sources to ensure you don’t put all your eggs in one basket.”

For a broken-egg example, Ulrich points to a contract the company signed with Oakland-based BrightSource Energy for a solar thermal plant in the Mojave Desert. The project crumbled when Senator Dianne Feinstein placed new environmental restrictions on the land.

Still, V. John White, Executive Director of the Center for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Technologies, doesn’t expect distributed solar to obviate large solar farms. “We have to recognize the scale of the energy we have to displace,” he says, “the [vast] amount of [renewable] energy we have to have to get off coal, and fuel electrical cars.”

The renewable piece of Edison’s power pie (close to last year’s state-mandated 20% milestone) is mostly made up of geothermal (more than half) and wind. Cooking up more solar makes a lot of sense because the panels produce the most power at essentially the same time — hot summer afternoons — that Californians demand it most.

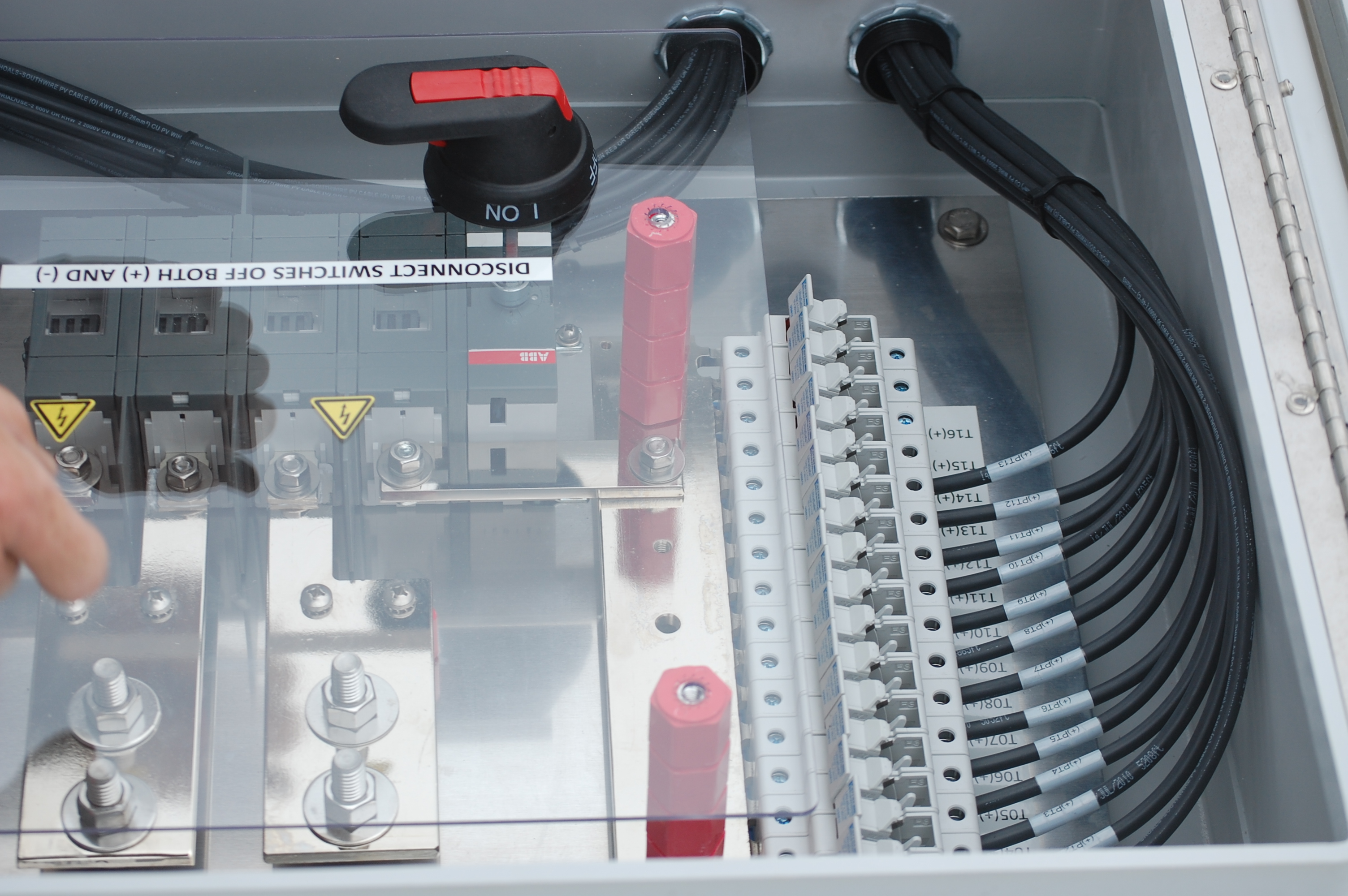

Although the solar panels on the Ontario warehouse look and perform like those on my San Gabriel home, the distributed solar project is something of an experiment. Pointing out a row of large inverter boxes, Rudy Perez says it’s still unclear how much photovoltaic can be loaded into a typical neighborhood electrical circuit without causing power fluctuations. “As clouds roll over you get into issues with intermittency that mean our output is going to be rising and falling fairly quickly.” The utility will study the issue in partnership with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Edison’s preliminary testing suggests the problem may not be as significant as some fear, in part because of the size of the project. Perez explains, “The nice thing about having so many buildings throughout an area is that as a cloud rolls over one building, it may be coming off another building, and the overall effect tends to balance itself out.”

Although the solar panels on the Ontario warehouse look and perform like those on my San Gabriel home, the distributed solar project is something of an experiment. Pointing out a row of large inverter boxes, Rudy Perez says it’s still unclear how much photovoltaic can be loaded into a typical neighborhood electrical circuit without causing power fluctuations. “As clouds roll over you get into issues with intermittency that mean our output is going to be rising and falling fairly quickly.” The utility will study the issue in partnership with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Edison’s preliminary testing suggests the problem may not be as significant as some fear, in part because of the size of the project. Perez explains, “The nice thing about having so many buildings throughout an area is that as a cloud rolls over one building, it may be coming off another building, and the overall effect tends to balance itself out.”

New smart meters the company is installing on customers homes could also help respond to shifts in power production. The devices have met with with less resistance in Southern California than to the north, in regions largely served by Pacific Gas & Electric.

4 thoughts on “Yes in Our Backyard”

Comments are closed.

bY THE END OF THE CENTURY, THERE WILL BE NOTHING LEFT IN OUR MINES TO MINE ( NATIONAL aCADEMY OF sCIENCES)

iT HAS BEEN CALCULATED, THAT IN ORDER TO BUILD SOLAR CELLS AND WIND TURBINES AT PRESENT ENERGY NEEDS, THERE IS INSUFFICIENT RAW MATERIAL TO MANUFACTURE THEM.

NUCLEAR IS THE MOST COST EFFECTIVE AND SAVE ENERGY. WE MUST NOT DELUDE OURSELVES OF A “PIE IN THE SKY” IDEA OF WIND AND SOLAR.

Solar power — all well and good IF YOU CAN STOP THE AEROSOL SPRAYING THAT IS CAUSING WHITE CLOUD HAZE AND SOLAR DIMMING. Advise everyone to look into geoengineering programs – solar radiation management, chem trails — see http://www.geoengineeringwatch.org or http://www.californiaskywatch.com — or You Tube – plenty of evidence of grid lines that become white haze — not from commercial jets.

@ Tex:

We won’t have to mine all new raw materials – there’s plenty recycled materials to fill most of our needs in terms of manufacturing new panels. Plus, as technology changes, less will be used more efficiently. Until there’s a better way to deal with nuclear waste, (and I doubt that’s even possible) then nuclear is too dangerous.

Great article KQED! Now start talking about feed-in tariffs and making ARRA funds available to the general public and local municipalities instead of the venture capitalist and corrupt corporations currently feeding off our hard-earned tax dollars.

Companies like Solargen Energy Inc., a startup with no experience in solar development, (their background is in oil drilling and ethanol production – two highly subsidized industries) qualify for millions, (in their case, $360 million) which then gets spent purchasing solar panels from China. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act money should be spent in America – not overseas.

Final note: The Chinese solar panel manufacturer Solargen is in contract to purchase up to 4 million panels from is a new startup as well. And they’re owned by Solargen’s major investor. Nice and tidy package for Solargen and the investor but the deal stinks for American taxpayers.

So sorry, I forgot to mention… Solargen proposes to build the largest utility-scale industrial solar project in the world in San Benito County, CA. It’s that kind of corruption and misuse of tax funds that makes distributed roof-top solar that much more attractive.

Thanks so much KQED!