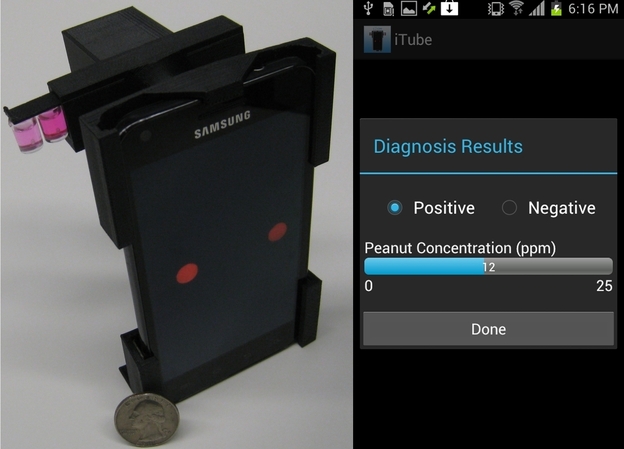

He envisions the iTube as a tool for schools, restaurants and, of course, parents of children with food allergies. Users of the minilab could upload their results to a personal database or share the results with people around the world to create a crowdsourced food allergy database.

Ozcan recently tested the iTube prototype with store-bought cookies and found that his device accurately identified the presence of peanuts. The results are published online in the journal Lab on a Chip.

Charmed as we are by this invention, we realized that when talking about life-threatening illnesses it would be good to talk to a doctor. So we called up Scott Sicherer, a researcher at the Jaffe Food Allergy Institute at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. He is not charmed at all.

"I definitely have concerns and skepticism and warnings for my patients who use any of these things," he told The Salt. "As far as I know, they are not accurate enough to rely on."

Food allergy apps on the market fall into three categories: food journals, to track foods eaten and symptoms; databases of food ingredients; and bar code scanners that can be used to determine food ingredients.

The food journals seem like they'd be harmless, since all the data comes from the person using them. But Sicherer says they could lead people to self-diagnose an allergy that isn't there and put themselves on needlessly restrictive diets. "Talk to a doctor" about symptoms, he says. "Don't try to diagnose yourself. That's where people get themselves into trouble."

A scan of available iPhone and Android food database apps reveals lukewarm reviews, with people noting inconsistency between the apps and actual product labels. Given how often food manufacturers change products and ingredients, it seems like maintaining an accurate, comprehensive database for an app would be difficult at best. Sicherer says: "When you're talking about your health and safety, you might not want to rely on that."

How about the bar code readers? They've been very successful for companies, such as Weight Watchers, that offer them to help people identify the calorie, fat, and fiber content in packaged foods.

But Sicherer dumps cold water on the notion of relying on these kinds of apps for finding potential allergens. "There's a big difference if you're deciding if something's going to send you into [life-threatening] anaphylaxis, or if the calories are higher or lower. The margin of error is different."

Unfortunately, Sicherer says, the most reliable and simplest thing to do to avoid food allergens is still to "read the label carefully, [and] ask questions in a restaurant."

Ozcan's lab on a phone looks like it could take care of the inaccuracy problem. But the prototype requires users to undertake a mini chemistry experiment. They would have to grind up the food, mix it in a test tube with hot water and a solvent, and then mix it with a series of testing liquids. That process takes about 20 minutes.

Imagine buying a brownie in a coffee shop and then going through that 20-minute drill. Suddenly asking the server "Does this have nuts in it?" seems like not such an ordeal.

Copyright 2012 National Public Radio.