Born in rural Southern California in 1922, Cunningham was a 50-year-old Walnut Creek wife and stay-at-home mother who had battled both agoraphobia and alcoholism when she met venerated cooking teacher and American arbiter of taste James Beard. She took his cooking classes, became his assistant, and turned him on to the charms of a funny little French restaurant in Berkeley, open for just a couple of years, called Chez Panisse. She wasn't a chef, she was a home cook, who shopped at the supermarket and liked to poke through other shopper's carts to see what they were cooking. No matter how her pal Alice Waters goaded her, she liked iceberg lettuce and drank black coffee with any meal, even in France. She still remembered the basic training of her high school home-ec classes.

Thus, when longtime cookbook editor Judith Jones gave her the job of revising the Fannie Farmer books, she knew that the new editions had to preserve Fannie Farmer's culinary heritage of good, plain, feed-the-family recipes, which had grown to encompass over 75 years of American cooking. At the same time, they also had to instruct a new generation of cooks who, perhaps for the first time, weren't learning to cook alongside Mom, because Mom had put on a blouse with a bow, or a hard hat and overalls, and gone to work. (In elementary school in the 70s, we still had home-ec classes, co-ed by now, as was wood and metal shop. As I recall, though, the curriculum imagined cooking as having the same usefulness as macrame. We shaped pizza out of biscuit mix, made peanut brittle, and were endlessly catechized about the correct way to wash dishes.)

Most importantly, the recipes had to work, to reassure cooks at all levels that they could rely on the big yellow books for any dish or menu. Her recipes might not have been the most adventurous, and they definitely weren't cutting-edge, but the ingredients were easy to find, the instructions were clear at every step, and the results reliable every time. Frost a birthday cake? Broil a steak? Roast a turkey? Make applesauce? Fannie, or more accurately Marion, was there to tell you. She didn't show off, but she knew everything you needed to know.

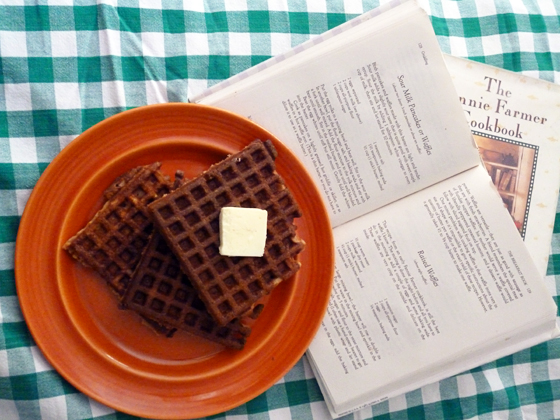

Those 800+ pages of Fannie Farmer became Cunningham's pedestal. She taught, wrote more books, including the sturdy, reassuring basic-skills book, Learning to Cook with Marion Cunningham, spread the gospel of light-as-air yeast-raised waffles (batter made the night before, left to rise on the countertop, then leavened again at the last minute with eggs and baking soda), wrote a longtime home-cooking column for the San Francisco Chronicle, worked as a restaurant consultant, tooled around San Francisco in her beloved Jaguar (bought with an early royalty check), and dined out frequently with friends, including her fellow Chronicle writer Michael Bauer, who took her along on numerous restaurant-reviewing forays.

Over the years, she generously mentored young chefs she believed in, from Zuni Cafe's Judy Rogers (whom she met when Rogers was cooking at the Union Hotel in Benicia) to Camino's Russell Moore and Bluestem Brasserie's James Ormsby. Baker's Dozen, which she co-founded in 1989, was part pastry laboratory, part support group and coffee klatch for (mostly) professional bakers, especially those writing books or articles for the general public. For her, getting to enjoy the company of family and friends around the table, sharing the everyday moments of life, was the real reason for cooking, and she emphasized this in every book she wrote.

Re-reading The Breakfast Book, which I've given (with waffle iron) to every newlywed couple I've ever known, I was charmed to discover her voice again, encouraging and surprisingly droll. After pointing out the importance of reconnecting with families at breakfast time, before the busyness of the day takes over, she later acknowledges that

"One of the most blissful escapes is breakfast in bed with something good to read. Breakfast in bed is cozy, quiet, and private. I instantly forget that it was I who fixed the tray."

Here, preserved and reproducible, are the old-fashioned, early-to-mid-century recipes that might otherwise be lost under the onslaught of GoGurts and Egg McMuffins: the Goldenrod and Featherbed Eggs, Date Nut Bread and Sally Lunn, Red Flannel Hash, Kedgeree, and Indian Pudding. It's also the home of that famous waffle recipe, whose delicacy and crunch may have less to do with yeast and baking soda than with the full stick of butter melted into the batter. (The recipe can also be found in the 1979 edition of Fannie Farmer.) Her California sensibility comes out with recipes for figs, persimmons, salsa verde ("as zingy and peppery as a mariachi band"), homemade yogurt and granola.

A few years ago, Neteler crossed paths with Cunningham. "I met Marion and told her the story and mentioned I still use my well-worn copy. She gave me a knowing smile and kind words."

She must have heard that story, or one just like it, hundreds of times over her 40-year career. But it pleased her every time.

Recipe: Yeast-Raised Waffles

This recipe is adapted from The Breakfast Book by Marion Cunningham. I've halved the amounts of butter and yeast called for in the original and suggested a mix of flours to give a little more textural interest to the batter. The slow overnight rise gives a slight sourdough tang to the waffles, making them a good choice with savory accompaniments like bacon or sausage.

Yield: 8 standard-size waffles

Prep Time: 10 minutes, plus 8 hours' rising time

Cook Time: 8-10 minutes

Total Time: 18-20 minutes, plus 8 hours' rising time

Ingredients

1/2 cup warm water

1 1/4 tsp (half a package) dry yeast

2 cups milk, warmed

4 tbsp butter, melted

1 tsp salt

1 tsp sugar

1 cup all-purpose flour

2/3 cup whole-wheat pastry flour

1/3 cup cornmeal

2 eggs

1/4 tsp baking soda

Preparation:

1. In a large mixing bowl (to give the batter room to rise), pour in the warm water and sprinkle in the yeast. Let stand to dissolve for a few minutes.

2. Add the milk, butter, salt, sugar, and flours, beating quickly until smooth and blended. (Cunningham attacks the lumps with a hand-held rotary, or egg, beater, a kitchen implement that's probably as archaic for the under-30 set as a rotary phone.)

3. Cover with plastic wrap and let stand overnight at room temperature.