I remember my first cookbook. It was Thrill of the Grill by Massachusetts-based chef and barbecue enthusiast Chris Schlesinger and former Gourmet editor John Willoughby. I was eleven or so, on the verge of vegetarianism, yet strangely fixated on the primitive allure of pit cookery -- a notable early contradiction in a life that has seen many. Before long, I graduated to a Jenifer Lang-edited edition of Larousse Gastronomique, Prosper Montagne's ancient and massive encyclopedia of (largely French) cooking techniques, traditions, and terms. I was learning French in school at the time, so dips through those thin, colorful, glossy pages dovetailed nicely with my foreign language studies. Other cookbooks followed -- Rick's Bayless's Mexican Kitchen, The Silver Palate Cookbook, and, of course, The Joy of Cooking. When I was moving out -- either bound for school, or for San Francisco, I hinted that I wouldn't mind taking a few with me. The Larousse, my mom informed me, was outside the realm of possibility; the Bayless, on the other hand, was doable.

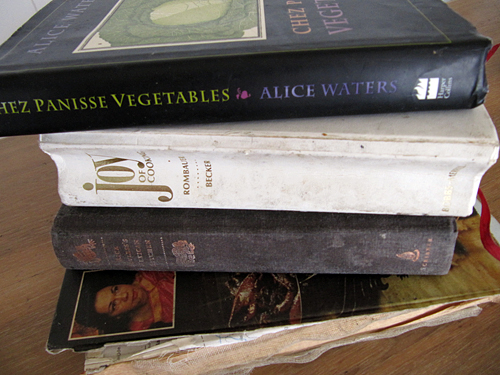

We form relationships with cookbooks, even magazines. We read them for enrichment and entertainment, and we also use them for a purpose -- to prepare specific dishes we're compelled to try cooking. When we learn how to cook something, the dish becomes part of our lives, and we carry the memory of making it along with the memory of enjoying it. I associate particular volumes in my collection with distinct periods of my life. When I was fifteen or so, an old, half-shredded copy of Charmaine Solomon's The Complete Asian Cookbook intrigued me with vivid descriptions of unfamiliar cuisines and ingredients. Simultaneously, it vaguely repulsed me with its weirdly unappetizing photographs. A year ago, I constantly flipped through Chez Panisse Vegetables; three years earlier, I pored over the gorgeous Silver Spoon, for the past 50 years, Italy's best-selling cookbook. My cookbooks -- some of them once my mom's, and a few of those perhaps her mother's as well -- are literally marked with the meals they enabled. Splashes of red and brown fleck a Marcella Hazan recipe for tomato sauce with mushrooms. The entire taco section of Mexican Kitchen looks like a grisly watercolor. They have been touched by hands and worn. Corners have been folded over; pen scribbles show that proportions have, for better or for worse, been adjusted. Someone I know writes the date next to a recipe when she's cooking from it, so she can look back at the book years later and see when she's cooked what. I usually try to sort that out by just dating the smudges. It's a field begging for an expert.

Current wisdom, however, holds that cookbooks are becoming obsolete. While food blogs and recipe-rich websites like Epicurious have been around, relatively speaking, for ages, most web-savvy cooks -- skittish about the potential havoc erupting pots and mishandled cutlery are capable of causing -- balk at positioning their precious laptops too close to a rowdy kitchen fray. Enter the iPad. I should say from the outset that I will never get one. They look ridiculous, too large and unwieldy to be truly convenient, and too small for comfortable typing. I am biased against it, but I cannot help but believe a significant portion of my skepticism concerning the iPad stems from having absorbed and rejected most vehemently widespread allegations that it's destined to revolutionize the universe of cookbooks.

Articles and blog posts salivating over the possibilities the iPad poses are hard to miss. Summarizing more than a few of those I've read would take a while. In late April, Gizmodo editor Wilson Rothman ably broke down the app onslaught in a New York Times Diner's Journal column, highlighting the best of what newly-minted iPad owners can expect from the warm plastic tablets: apps like Epicurious and BigOven brimming with grocery list-making functions and interactive aids paving the way for digital app-ified versions of seminal cookbooks.

While at least one person has proven enthusiastic enough to install an iPad in his kitchen cabinet, app-mania drives me a little nuts -- and not just because I can't afford to spend half a grand on a gadget. I can't deny that it must be nice to cook with such a wealth of information at one's greasy fingertips, but there's something so temporary and soul-less about technology's ability to put reams of information into a very small space. I can draw an obvious parallel to collecting vinyl. I own an iPod shuffle I bought for $50 three years ago, but I still purchase vinyl records, and won't stop -- even though digital music is, at this point, practically free. As a matter of fact, I don't feel like I actually own an album unless I have it on vinyl. It's not simply a proprietary longing; without the actual record, music feels ephemeral to me, as if it might suddenly blow away. The comparison doesn't entirely hold up though: Vinyl records actually sound better than mp3s of the same songs, whereas a recipe's usefulness doesn't depend on its packaging, particularly when an iPad can call up ingredient profiles, recipes, and instructional videos with a few brisk clicks. The truth is usefulness doesn't really encompass the point of a cookbook. Like album art, a cookbook can be stylish, beautiful, and evocative -- something people want to display, cherish and share. Any publishers of cookbooks banking on digital downloads down the road shouldn't forget this.