Many Americans are what All The Rain Promises And More author David Arora calls fungophobic. I started this thin volume on a red-eye flight from San Francisco to New York City several years ago. I'd intended to become an overnight edible mushroom expert. Unfortunately, pills and $6 Heinekens clouded my concentration around the time I thumbed past the introduction, and I soon folded up the book and bopped off into a restless, heaving slumber. As a result, I know little about mushrooms -- their identification and classification. The introduction, however, I do remember, particularly a section in which Arora briefly outlines fungophobia. Now, every fall, when wild mushroom season booms, associations resurface. I think about what mushrooms represent -- to me, a life-long seeker of tasty edible fungi, as well how they've been conceived by others over time.

Arora claims our fungophobia came -- like bowl cuts and breakfast links -- from the British, who believed mushrooms were nutritionally worthless and perhaps hostile by design.

The Roman Stoic Seneca may have rather poetically dubbed them a "voluptuous poison," but for thousands of years, in less fearful cultures, mushrooms have been used in the crafting of folk medicines. Lest that fact be relegated to the territory of bubbling cauldrons, pockmarked witches, and spooky incantations, more recent research has linked some of the same mushrooms with cancer-fighting properties, anti-pathogenic activity, and immune system enhancement. Penicillin, along with many other famous pharmaceuticals, comes from the fungi kingdom. Nutritionally, mushrooms are no sweet potatoes, yet many are still high in fiber and provide vitamins like thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, and ascorbic acid -- as well as minerals such as potassium and phosphorus. Exempting those that kill you or make you crazy for six hours, wild mushrooms can, as most readers are very aware, be extremely delicious. Chanterelles are buttery and subtle; fresh porcini are robust and nutty, excellent roasted, or in salads with Parmigiano-Reggiano shavings and pine nuts; lion's mane mushrooms are furry and high-strung, delicate, with a mild, almost seafood-like taste -- especially nice folded into an omelette. The possibilities are nearly limitless, and most dedicated eaters and chefs prize their special qualities and bountiful culinary applications.

But lore is stacked against mushrooms -- and not just because a few of them are quite dangerous. Historically, mystery and sheer perceived strangeness have had as much to do with the stigmas surrounding their consumption as the bloating, vomiting, and painful death certain varieties tend to cause. In medieval Ireland, people thought leprechauns used them as umbrellas. The ancient Egyptians believed mushrooms were the sons of gods, zapped to earth on tremendous bolts of lightning. The English imagined they had to be gathered under a full moon in order to be eaten safely. Mushrooms are weird: fragile, oddly luminous products of darkness and moisture that spring up unannounced -- like magic -- in woodsy crevices. That may have been why people were once so alarmed by them. They don't grow like wild and cultivated plants. Centuries ago, in Western Europe, mushrooms were sketchy pagan symbols, ominous harbingers of supernatural forces -- particularly when they were discovered suddenly sprouting in circular "fairy ring" colonies. Today, from Victorian paintings and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland to Fantasia and the distinctive cap-and-stem-like cloud that forms in the wake of a massive explosion, mushrooms are iconic, but not a food with universal appeal.

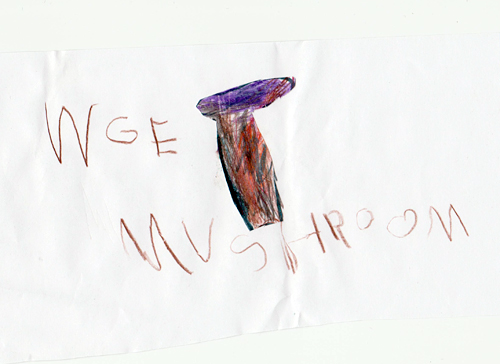

Last week, when my pre-kindergarten class was making its weekly foray through the Ferry Building, we stopped at the Far West Fungi store. We'd been there on other occasions, to scope the spore logs and posters, but I was freshly inspired. I'd made very good use of the season's offerings the night before -- skillet-browned porcini, king trumpet, chanterelle, and oyster mushrooms on a crispy pizza with thyme and Bellwether Farms Crescenza -- and was wondering how their bizarre shapes, fetching names, and earthy flavors would go over with the kids. I arranged a few raw ones on the art table for them to draw -- lion's mane, chanterelle, trumpet, and oyster -- and sliced and sauteed the rest in butter with a pinch of salt while the children napped. An hour later, for snack, in addition to cheese and crackers, I passed a plate with four glistening beige-and-brown mounds for them to sample.