The fig tree in my neighbor's yard--the one with lots of branches hanging temptingly over the sidewalk--is just starting to ripen its fall crop. According to California law, fruit growing in public space (hanging on a branch over a city sidewalk, for example) is public fruit, and free for the taking, as long as the picker leaves what's on the other side of the fence (or property line) alone. Going out to get yogurt and a newspaper on a Saturday morning, I'd arrive home with a foraged breakfast centerpiece of ripe sweet figs.

The fig tree in my neighbor's yard--the one with lots of branches hanging temptingly over the sidewalk--is just starting to ripen its fall crop. According to California law, fruit growing in public space (hanging on a branch over a city sidewalk, for example) is public fruit, and free for the taking, as long as the picker leaves what's on the other side of the fence (or property line) alone. Going out to get yogurt and a newspaper on a Saturday morning, I'd arrive home with a foraged breakfast centerpiece of ripe sweet figs.

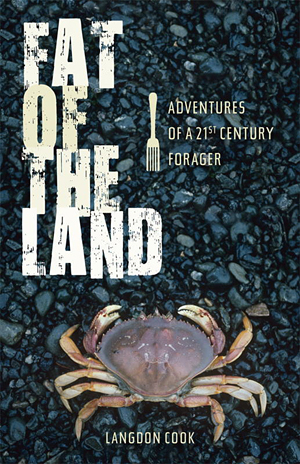

But clearly, I've barely cracked the spine on Foraging for Dummies. At least compared to Seattlite Langdon Cook, author of Fat of the Land: Adventures of a 21st Century Forager for whom a daily forage might involve digging for razor clams at dusk in December, or setting up a spotlight for late-night squid jigging in January. Spearfishing for lingcod within the city limits, hand-grabbing Dungeness crab out of the Sound, dodging homeless guys to harvest choice young dandelion greens near the I-5 on-ramp. . . if you sum it up like that, Cook sounds like a pretty wild and crazy guy.

Except that he's almost always eclipsed in his own narrative by the buddies who show him the ropes. With nicknames like Trouthead and Warpo, these dudes are guy's guys, passionate, risk-loving, obsessive hunter-gatherers who let Cook tag along as they head into their element: to the bank of the Columbia at dawn for shad, into a beat-up canoe on the Hood Canal for shrimp, tramping a burnt-out section of the Okanogan National Forest for morels.

Cook walks the walk, and dives the dive, but hard as he tries, he never quite transcends. Throughout, he remains a game but nerdy writer, less on the hunt for shrimp and sturgeon (the toothy, prehistoric-looking fish that Cook's friend Beedle describes admiringly as "one tough hombre") than for a certain manly authenticity that remains always a little out of his reach, no matter how many times he grabs for his pen to scribble down a colorful phrase.

"What can be said about this river that hasn't already been said?" he notes from the banks of the surging Columbia River, looking up at the power lines swooping overhead. "I try to put myself in a dugout canoe circa 1805, but the wires keep getting in the way."