Erik Larson has a history of turning the history we think we know into compelling stories that keep us on the edge of our reading seats. In The Devil in the White City, he found a serial killer at the heart of the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. In Thunderstruck, he turned the invention of the radio by Marconi into a trans-Atlantic chase thriller. With In the Garden of Beasts, his readers witnessed, through the eyes of the American Ambassador and his family, the transformation of Germany into a Nazi state shortly before World War II.

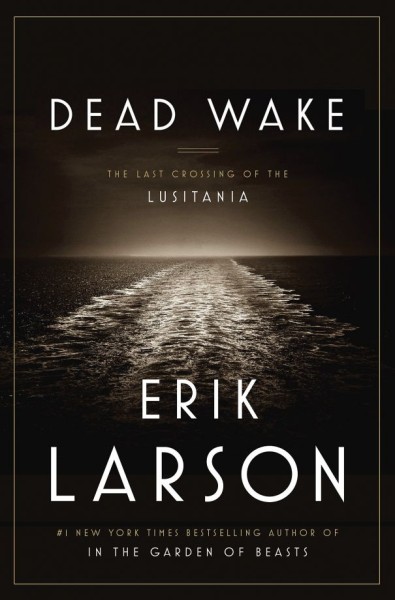

Larson’s gift for turning historical events into works of non-fiction that read as novels reaches a new level with his latest, Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania. He’s always managed to craft nail-biting suspense from the so-called lessons of the past, but this time around, he finds not just tension, but romance in the ruins. It adds even more depth to his already complex canvas. By using the literary toolkit of novel-length fiction, Larson is able to evoke not just the facts, but the emotional truth of the past.

I caught up with Larson before his upcoming appearances to get a preview of the book and the means by which he crafted it.

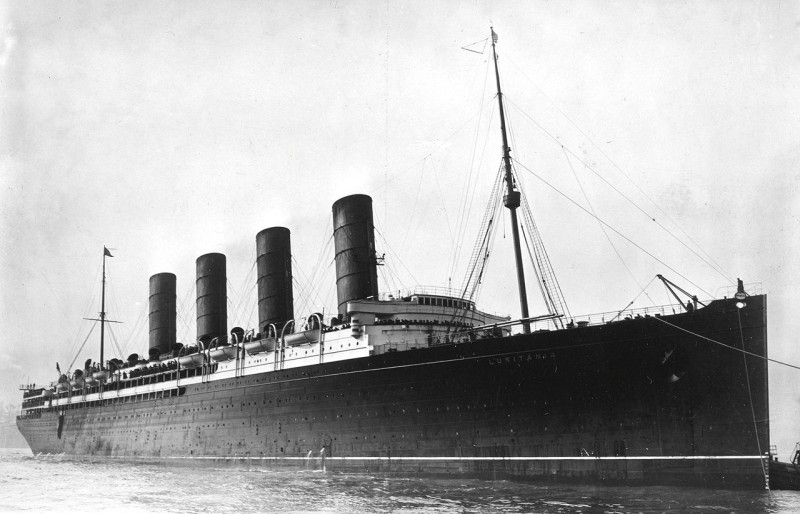

Your historical works of narrative non-fiction often turn on the impacts, both intended and unintended, of new technologies. Were there technological innovations at work in the story of the Lusitania?

Your historical works of narrative non-fiction often turn on the impacts, both intended and unintended, of new technologies. Were there technological innovations at work in the story of the Lusitania?

Very much so. The submarine was a wholly new weapon at the start of the first World War, one that neither the British nor the Germans at first understood. One unintended consequence was that it led Germany to discard century-old rules governing naval warfare against civilian ships, in particular a long-honored, outright prohibition on attacking passenger liners. In the end, this proved a fatal consequence for Germany, not because of the Lusitania attack itself, but because of a series of submarine attacks against American flag vessels (the Lusitania was British) during the two years after the sinking, as well as the so-called Zimmerman Telegram, which together drove President Wilson to at last realize that America could no longer sit on the sidelines.