Warning: This episode contains explicit language.

View the full episode transcript.

Michelle Cruz Gonzales spent her teenage years and the beginning of her adulthood immersed in the Punk scene in the East Bay. She performed under a stage name, “Todd,” in two iconic, all-female groups: Kamala and the Karnivores, and then Spitboy. While Spitboy was active, they toured multiple countries including Canada, Italy, England, and Japan. After Spitboy split in 1995, Gonzales and two other members of the band continued to perform for a few years, under the name Instant Girl.

While Gonzales enjoyed performing, she often had to deal with an indifferent, colorblind attitude from others who didn’t seem to acknowledge racial and ethnic differences: She says, “Punk rock, I think, put some barriers in between me and reclaiming my chicanisma, because I was so kind of, concerned with being in the band, fitting into the scene. I didn’t want to be invisible, but also, you know, there’s this whole system of things that are put into place, that if you’re a person of color, you could easily not be noticed.”

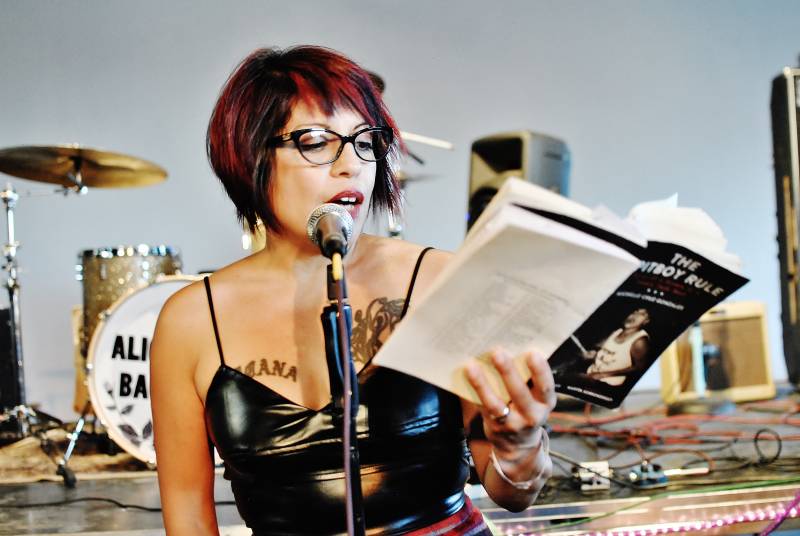

Gonzales went on to write about her experiences in her memoir, The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band. The book features a series of vignettes, pulled from moments in her life, detailing performances and dealing with sexism from concert goers, how the band formed, how she started performing, and more. Now, Gonzales is an English professor at Las Positas College, and teaches courses with other books that were written by punk musicians and artists.

When asked how it feels to see a new generation of people keeping the punk scene alive, Gonzales responded, “It just makes me happy that the scene is like, thriving, and that kind of art is still important. It’s not about it being a zine. It’s not about it being a band. It’s about it being independent. It’s about that there’s this third space for young people that supports these ideas for young people, and encourages young people to not wait for some Columbus to come and discover them.”

The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band is currently available through both Amazon and PM Press.

Episode Transcript

Sheree Bishop, host: Hey y’all, it’s me, Sheree, the production intern on Rightnowish. I’m back with another episode. This time, I got to speak to punk writer, Michelle Cruz Gonzales.

Michelle Cruz Gonzales, guest: I was already viewed as a freak as a person of color in the small town I grew up in. And I was just like, fuck it,y ou know. If you think I’m a freak, I’ll show you a freak. I’mma be a fucking freak. I’ll be in a band of women that just yells and screams in your face. I’ll be a girl who plays the drums. [gasps] Oh,God forbid, oh so scary!

Sheree Bishop: As a teenager, Michelle started performing in a band called Bitch Fight. Then as an adult in San Francisco, she performed under her stage name “Todd” first as a guitarist in Kamala and the Karnivores, and then as a drummer for Spitboy. Both of these were iconic, all-female bands. Spitboy was unlike a lot of bands at the time, because their lyrics were a blunt response to unchecked sexism.

For those of you who don’t know, San Francisco’s East Bay is widely considered one of the epicenters of punk music. It’s home to venues like 924 Gilman and the nationwide zine Maximum RocknRoll. Many now-famous bands got their start right here in the Bay, and then went on to gain fame and notoriety across the country, and in many cases, internationally.

Michelle’s memoir, The Spitboy Rule, talks about being a Xicana woman in this same East Bay scene that, at the time, didn’t seem to recognize her for who she really was.

In 2016, her book joined a roster of several ones written by punk musicians from the Bay. Books like these document the history of a culture that has deep roots here, from a perspective that often gets erased.

We’ll talk about how Michelle found herself through performing, feeling seen as a person of color, and more, right after this.

Sheree Bishop: For people who don’t know, never been, paint the picture of like a typical show. What are like some details? What does it look like? We all know what it sounds like. Where do you fit into this picture?

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: A lot of the shows I went to were at Gilman and, um, the stage is a funny shape and there’s this one side on the right that’s kind of, um, off to the side because the shape is, the shape of the stage, they’ve changed it recently, had like a narrower end on the right side when you’re standing looking at the stage

I would often be on that side, away from the mosh pit, because, you know, even though, you know, they had rules at Gilman, they still do, about, you know, no sexism, no racism, no homophobia, et cetera, no alcohol and all that, um, there were a lot of guys who would try to grab your boob or like touch you, you know, when they were going around in the pit and just be disgusting. And I would like, I would wind up getting in fights or almost fights with those guys and so rather than escalating the situation, I would just try to stand on the side.

I also didn’t really care that much for moshing. I’m five feet tall. I don’t, I don’t really want to like, be smashed around.

Right after Bitch Fight and before Spitboy, I hung out with this group of girls, super multicultural group of girls, who all love to dance. And we would go to every single Operation Ivy show. We’d go to every Crimpshrine show. We’d go to every Green Day show, and we would be in that little corner where we wouldn’t get moshed into, or no one would grab us, and we would just dance.

And that was, I think, those are some of my funnest times at Gilman. You know, I wasn’t having to worry about playing, or being on stage, or setting up my drums, or guys, you know, saying dumb stuff to me like, “Oh, you hit really hard for a girl,” um, stuff that people would say to me after shows. Um, that was a more carefree time before I was in a band, after Bitch Fight, before Spit Boy. We were just there to support the bands and support the music.

Sheree Bishop: You’ve performed in a lot of places, literally all over the world.

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: Yep.

Sheree Bishop: What sets East Bay punk apart?

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: I think what sets it apart is it, it was born out of, among other things, like Maximum RocknRoll, Gilman Street was born out of a desire to create a safe punk zone for young kids who were into punk.

And 21 and over clubs weren’t safe, well you couldn’t get into them. And then you had these other smaller shows where there were a lot of fights and a lot of violence. And, you know, just like a lot of, like, toxic male energy that was tolerated. And, um, Gilman Street wanted to create a place where that wouldn’t be tolerated so people could like go to shows and have fun and not feel unsafe. Even though we didn’t talk about gender issues enough and even though we didn’t talk about people of color issues enough and everyone was all like, “Oh, I don’t see race.I’m colorblind.” I’m like, ‘oh, that’s weird.’ Even though that was happening, people also didn’t shun you and didn’t exclude you.

We had people of color from all different backgrounds. We had older people like Murray, you know, rest in peace, Murray, who, you know, who guided us and made us feel safe, but also were like artists and like, had jobs and he like, took all the photographs and documented everything.

And there were other people at Gilman, like Pat, who also passed away recently, who looked out for the young people and no matter who you were or what your background was. I think that really made it different. It wasn’t just a club where where they were trying to make money. Gilman was always way more than that so I think that’s totally what distinguishes it.

[Music]

Sheree Bishop: Gilman is still active today and like you said, a little different and stuff like that. And so I’m wondering, like when you see folks in the East Bay today and they’re doing shows, they’re making zines, they’re doing the same things that you and your friends and your peers did, what, like, feelings does this bring up for you to see people doing the same thing today, especially women of color?

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: Um, I mean it makes me so happy that punk is so black and brown now. And the fact that we have bands like Deseos Primitivos in Oakland, who sing in Spanish, You know, there’s so many bands with women in them now, um, queer folks in bands, you know, who are, who are out, um, trans folks in bands.

Keep making zines, please, because some of the best new ideas and art, you know, is in zines.

Um, so it just makes me happy that the scene is like thriving and that kind of art is still important. Um, and it’s not about it being a zine. It’s not about it being a band. It’s about it being independent. It’s about that, that there’s this third space for young people that supports this ideas for young people and encourages young people to not wait for some Columbus to come and discover them.

Sheree Bishop: This seems to have like taken up and defined like a huge chunk of your life. And so to see people like, having obviously not the same, but experiences with similar music in the same places, um, that’s, that’s really cool, that it’s like, still bringing you joy, even when you’re not actively doing it.

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: Totally, and now, as a community college, you know, writing and English professor, I’m teaching like, punk memoirs. I’m teaching James Spooner’s book in two of my classes, and you know, introducing these ideas, um, to young people at the community college level. I don’t know why. Like, after my sabbatical recently, I was like, why am I not teaching any punk books? I mean, there haven’t been that many for, you know, for a long time there weren’t that many.

Now there are so many more punk memoirs and literature and, um, punk is, is a more mainstream idea or concept now. It’s more socially acceptable and that’s not why I’m teaching it, but I, for some reason before I didn’t even think to do it. And now I’m like, young people, of course, like young people are trying to figure out who they are and they’re feeling rebellious and punk rock is doing all those same things. Like why not teach about punk in my, in my literature classes, in my English classes?

Sheree Bishop: In your memoir, you mention a lot of these instances of just hecklers. Like you would be in the middle of introducing a song in the middle of playing, and people would start to say stuff that just didn’t make any sense and just was like very derogatory and like rude. And so I’m wondering, like, what did your experiences in Spit Boy teach you about like, dealing with people, especially people who feel the need to insert themselves like that?

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: A lot of those comments were really sexist because it was just so threatening for, you know, punk rock, hardcore punk rock dudes at the time to see women on stage. And again, we were, you know, giving our gender studies lesson at the same time, which was not appreciated. Apparently they just wanted to mosh. I just feel like the things that it taught me were….

Sometimes you just have to, like, get mad and give it back to them. But it, it also just taught us, and me, that there are a variety of different ways you can respond, and um…sometimes the best answer is for me to just click the song in and play the song as the answer. Oftentimes the song that we are about to play just addresses, you know, the sexism in the room just as well.

A lot of those experiences were really traumatizing, and there were times when we cried our eyes out afterwards. I’m not going to say that like, those people should have done that so we could toughen up, definitely not. But, it does teach you a lot. It really does.

Sheree Bishop: Did you ever feel like you were othered within the scene? And what did those moments look like for you?

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: I didn’t really expect to be othered in the scene, you know? Um, I remember there’s this kind of scenester guy and he was like talking to me and he said, “Oh, you’re like the whitest Mexican I ever met in my whole life.

[Music]

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: And I was like, Oh, yikes, I don’t, don’t say that. I mean, I didn’t say that to him. I actually just said nothing and swallowed it and just felt really awful about myself.

And then I remember just times where I really, you know, you hear people talking shit about people of color, Mexicans, or just making racist jokes. You realize, like, whoa, they don’t, like, do they know I’m in the room? Am I, like, invisible to them?

I also just remember a lot of times where I really wanted to, just naturally, wanted to just be all the different selves that I am, and not have to, like, separate them all, all the time and feeling like I couldn’t do that because, um, we had this, this informal system, punk points. And it was a joke. It was supposed to be a joke. Like, we would, people would say, like a lot of the dude scenesters would say like, “Oh, you just lost your punk points because, you know, you grew your hair long,” or so and so “lost their punk points because, um, we found out they’re from Walnut Creek,” or whatever, you know. And punk rock…that was one of the reasons why I broke up with punk rock, like, briefly.

I just remember, like, I would always cut my hair really short and then grow it long, cut it short and grow it long. And I remember every time I grew it long, it was because I felt like nobody really saw who I was. No one really…they just saw me as Todd, the drummer of Spitboy, and not like Michelle Gonzales, not like the Xicana who I am.

Sheree Bishop: You mentioned that punk exists as this like, third space that’s free from capitalism and consumerism. So what happens when materialism and consumerism does seep in?

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: Well, I mean, consumerism sneaks in all the time because we’re part of the larger culture. But punk does, can, does, can, and has existed as a third space, um, where people sometimes are trading, um, goods, um, selling their own wares without, you know, a middle person or an agency or a company that they have to pay back or anything like that.

I think the result of materialism in a lot of ways has been that a lot of those pop punk bands that are like, are punk…. they call themselves punk, but they’re like, mainstream. And they- a lot of them just sound totally alike. That to me is one of the main like, things that I’ve noticed. That materialism creates kind of like a stereo- a punk stereotype and, and rolls with the punk stereotype, like hard and fast music, and, um, you know, people drinking, and like, you know, maybe being too rough, getting into fights, very kind of like, kind of like, just kind of this toxic male energy thing that, that um, the media likes to latch on to, materialism likes to latch on to.

Like, we were a message first band. Spitboy was never going to make it on a major label. We would have never changed who we were. We would have never become this, like, girly, beautiful, you know, gussied up band. That wasn’t our aim, but I don’t fault anyone else for… for having a different strategy.

We need to support artists, just no matter what, I mean, whether it’s punk or whether it’s jazz. My son is a jazz musician. We need to support the arts more, um, across the board. That takes money to a certain extent. That takes materialism and capitalism, right? So it’s a… it is a conundrum.

I don’t have the same kind of ideas that a lot of punkers have about, um, quote unquote selling out.

[Music]

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: Like, my favorite band is The Clash. Everything I learned about politics as a teenager was from The Clash.

If they hadn’t quote unquote sold out, I wouldn’t, I grew up in a small town, I wouldn’t know, I wouldn’t have known anything about Nicaragua, El Salvador, I wouldn’t have learned about imperialism in Afghanista., I mean, there are just so many things I learned from The Clash because they sold-they were on a major label and I was able to buy their records from Value Giant, you know, in Tuolumne or whatever.

And then my grandmother, my sister’s grandmother, like, bought me a couple of Clash records for my, for Christmas because that’s what I wanted. She was able to go to the mall and get them. You know, if they hadn’t sold out, I wouldn’t have had access to them and to their ideals, which um, were instrumental in shaping my politics, my values, and, and all of that.

Sheree Bishop: I also wanted to know how did being an East Bay punk affect your perception of yourself? If you weren’t like, how do you think your perception of yourself would be different?

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: I didn’t grow up in a town with a, with a Latinx or Latine community. I grew up in a really small town in California in the Gold Rush country. I mean, there are like 700 people in the town that I grew up in. So moving to the Bay Area changed my sense of identity.

I went in and out of trying to figure out how could I really be myself, um, and, and not also not really understanding what that meant because I was born in LA. We’d go visit my family and, you know, everyone speaks Spanish there and I didn’t grow up speaking Spanish. And, um, I really felt such a strong pull to my like Chola cousins and my grandmother, who was bilingual.

But at the same time, I didn’t grow up in that. So like my way of expressing my Mexicanisma was, you know, just largely through food growing up and then I moved to the Bay Area and I just felt like… like I just had to try to fit in as much as I could to punk rock because I was so tired of being bullied and wanted, I wanted a community. I wanted to fit in and I couldn’t move, I wasn’t going to move to L.A., that wasn’t like… I was a band, I was here.

Punk rock, I think, made it… put some barriers in, in between me and reclaiming my, my Xicanisma, because I was so kind of concerned with being in the band, fitting into the scene. Not… I didn’t want to be invisible, but also you know, there’s this whole system of things that are put into place, that if you’re a person of color, you could easily not be noticed. Like, a lot of the time you went by your first name, and then your band name. So I was always Todd Bitchfight or I was Todd Spitboy. I would hardly ever use my last name. Finally, at one point, we all decided we wanted to use our last names on our record, and I was so happy and so relieved because I finally got to, like, put it out there that my last name is Gonzalez.

[Music]

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: I do remember there was this woman, a friend of Karen, our guitar player, and she said the nicest thing that anyone’s ever said to me. She asked me what my last name was, and I told her, and she said, “Oh, are you Mexican?” And I was like, Oh, and I just was like, ‘Yeah, I am actually,’ and she’s like, “Oh gosh, I don’t know why I didn’t realize that until just now until you said that.” I said, ‘What do you mean?’

And she said, “Well, you know, like in punk, I guess it’s just like we all just like go around being all like punk rock and like, you know, our first names and not really talking about our families or our backgrounds that much.” I mean, she said something along these lines. And, um, she’s just like, “I just want to say, I’m really sorry, I didn’t realize that sooner. I should have, I should have seen that on my own,” and I was just like, oh my gosh, no one had ever said anything to me like that.

Sheree Bishop: How did it feel to like, feel seen like that? And have you had, like, any other moments like that?

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: [laughs] Um, felt really good. I mean, that was the thing about it. It felt really, really good. I was like, wow, like this is a thing. Like I didn’t even know that was the thing that, that another person could really see me and make me feel that good, and also like, apologize for her privilege or take responsibility for her privilege.

And this was before people were talking about white privilege. This was before people, like, felt like there was any need to, like, you know, accommodate other people other than, you know, the dominant culture. So it really, it really felt, it felt great. And it was a, it was a real kindness.

Sheree Bishop: I love that. I love that so much. It’s like one of those moments where it kind of like, opens up like your world a little bit because you resign yourself. And you’re like, that’s not gonna happen, like I have to keep this separate, like, they’re not gonna care, but it’s like people do care and people might also care if you like are open about the parts of yourself that you can’t change and that people choose not to recognize, so.

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: And I think that’s the thing, you’re hitting on something really important, that is, if we’re our authentic selves, people will appreciate that. Um, I mean, of course there’s racism and all that, but like, people in your communities, even if they’re not comfortable completely with different backgrounds that they’re not familiar with, if you are who you are, if you’re authentic, um, that will make you more human, in the very least.

[Music]

Sheree Bishop: I want to give a huge shoutout to Michelle Cruz Gonzales. You’ve accomplished so much just by being who you are, and being an in your face artist, regardless of what other people want to say.

Michelle’s memoir, The Spitboy Rule, where she talks about performing all over the world, is available on Amazon or directly from the publisher, PM Press. If you’d like to see what she’s writing right now, you can check out her website, https://punk-writer-michelle-cruz-gonzales.com, which is written with a dash between each word. You can hear music by Spitboy, and Kamala and the Karnivores on multiple streaming platforms.

This episode was hosted by me, Sheree Bishop. Chris Hambrick is our editor. Christopher Beale is our engineer. This episode was also made possible by Pendarvis Harshaw and Marisol Medina-Cadena

The Rightnowish team also includes Cesar Saldaña, Katie Sprenger, Ugur Dursun, Jen Chien, and Holly Kernan.

Take it easy, and don’t forget to support the musicians, writers, zine makers, and other artists in your area. They’re doing all kinds of cool stuff, literally all the time.

Rightnowish is a KQED production.

Rightnowish is an arts and culture podcast produced at KQED. Listen to it wherever you get your podcasts or click the play button at the top of this page and subscribe to the show on NPR One, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, TuneIn, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.