Anyone who’s lived with someone experiencing addiction — or dealt with it themselves — knows how it can plunge entire families into chaos. The damage feels personal. While experts agree that addiction often stems from other types of suffering, we have yet to contend with how collective trauma might factor into today’s overdose epidemic.

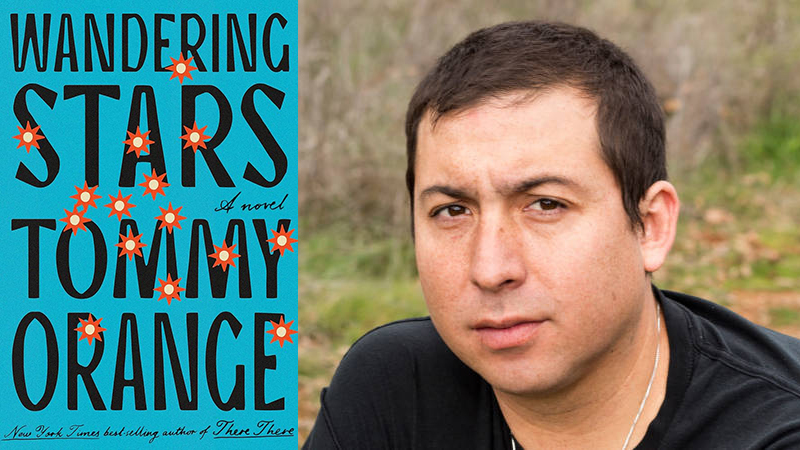

In Oakland author Tommy Orange’s capable hands, addiction that stems from the United States’ violent past and present comes into sharp focus. Orange’s new novel, Wandering Stars (out Feb. 27 via Knopf), tells a story, a century-and-a-half long, of a family descended from Jude Star, a survivor of the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864. After most of Star’s community is brutally murdered, white colonizers imprison him and subject him to violent, forced assimilation. He ends up drinking to cope with a psychic wound so deep that it ripples through six generations.

Orange himself is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes; his ancestors also survived the Sand Creek Massacre. He chose addiction as the throughline of Wandering Stars because of its impact on his own family.