Sure, America might have a whole gamut of food celebrities: David Chang with his hard-edged braggadocio, Alton Brown’s affable nerdiness, Ina Garten and her aspirational East Hampton aesthetic. But we don’t have anyone quite like Nigella Lawson — or, simply, “Nigella,” as the London-born-and-raised cookbook author and television chef is known in the U.K., where her iconic status is hard to overstate.

In the 20-plus years since she wrote her debut cookbook How to Eat (1998), Lawson has built up a dedicated fanbase by being an outspoken proponent of the sensory pleasures that can be found in cooking and eating. She is “Lady Bountiful, a sensualist celebrator of appetite,” as a recent Guardian profile put it. A journalist by training, Lawson speaks and writes about food with a poet’s ear for language in even the most seemingly tossed-off of comments. Who can forget the time when, as a guest judge on Top Chef, she described a panna cotta as having the “quiver of a 17th century courtesan’s inner thigh”?

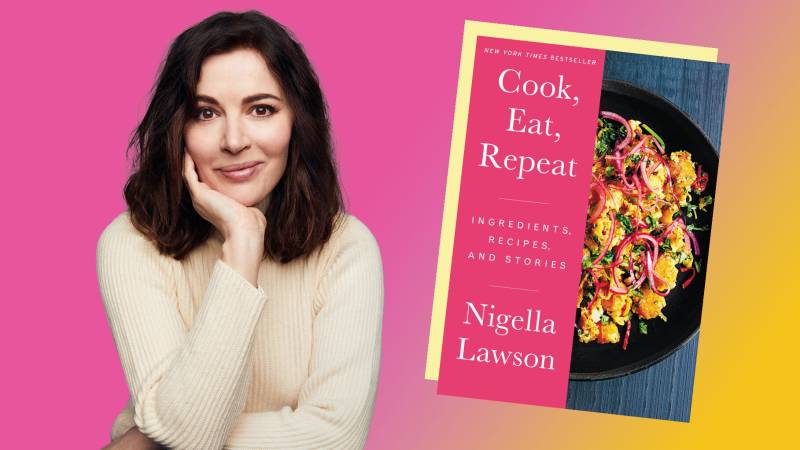

Cook, Eat, Repeat, Lawson’s latest collection of essays and recipes, is packed with similarly lovely, discursive writing. It’s organized around a handful of wide-ranging themes and ingredients that interest her. Instead of having, say, a section for breakfast recipes and another for dessert, there’s a chapter on why she hates the term “guilty pleasure” — and an accompanying set of recipes that instead lean into the pleasure. There’s an entire chapter’s worth of anchovy recipes. And yet another on rhubarb.

Written mostly during the early months of the pandemic, the book — and Lawson’s BBC cooking show of the same name — talks about cooking not as some big performance that you put on for the sake of others, but rather a set of small, repeated tasks that you weave into the course of your day. Something modest that’s worth celebrating.

The book was first released in the U.S. in April of last year — right when the Delta variant surge made it unsafe to launch an overseas publicity blitz. So, now, Lawson’s making up for lost time with an extended book tour that arrives at San Francisco’s Sydney Goldstein Theater on Monday, Nov. 14.